CAP Prize 2020 | Shortlist

CAP PRIZE 2020 | SHORTLIST

The following 25 projects – in alphabetical order by artists last name – were selected by the CAP Prize panel of judges comprising 18 international curators, editors, publishers and artists, from hundreds of applications for the CAP Prize 2019. Five of the shortlisted artists will be awarded with the CAP Prize 2020 for Contemporary African Photography to be announced at photo basel in September 2020.

The shortlist comprises works by: Alia Ali | Roger Anis | Ramzy Bensaadi | Flávio Cardoso | Margaret Courtney-Clarke | Cesar Dezfuli | Rahima Gambo | Gianluigi Guercia | Skander Khlif | M'hammed Kilito | Seif Kousmate | Nora Lorek | Gosette Lubondo | Mehdy Mariouch | Frédéric Noy | Lee-Ann Olwage | Onwumere Chukwudi | Gloria Oyarzabal | Lynn | Ugo Woatzi | Ismail Zaidy | Fares Zaitoon

The call to the 10th CAP Prize will open 7 November 2020.

Alia Ali

Born in 1985 in Vienna, Austria. Lives in Marrakech, Morocco

www.alia-ali.com | Instagram: @studio.alia.ali

Flux, 2019

Yemeni-Bosnian artist Alia Ali explores cultures at geographic crossroads. Her work considers how politics, economics, and history collide in fabric patterns and techniques, showing how fabric both unites and divides us.

Focusing on wax print fabric—a form with roots in Indian, Japanese, Chinese, Javanese, Dutch, and African traditions—FLUX captures the way textiles move and migrate across different cultures. This series of photographic portraits present people who are at once concealed and highly visible, their silhouettes warped by textile patterns, their faces covered over by vibrantly colored fabrics.

Surrounded by upholstered frames, these portraits convey both the intimacy of fabric—a material worn close to the body—and the way its seductive colors and prints often obscure the violent colonial history and exploitative global economy. Reflecting on how wax prints came into existence across borders, FLUX reveals how these histories are woven into the very processes and production of the wax print. The resultant portraits evoke the cultural flux resulting from today’s mass migrations and increasing geopolitical instability across the world.

These fabrics in flux are a commodity once considered as precious and as commonplace as gold, frankincense, myrrh, jewelry and, as previously mentioned, humans. FLUX questions the very nature of how things get named, how they are translated, and how, eventually, are reinterpreted. Furthermore, it questions the intention of their production. If it is not for the preservation of heritage, then is it for the propagation of economic wealth? And for that matter, whose wealth?

Roger Anis

Born in 1986 in Cairo, Egypt. Lives Cairo, Egypt

www.rogeranis.photo | Instagram: @rogeranis

Relationships in Captivity, 2017

The government-run Giza Zoo in the heart of Egypt's chaotic, polluted capital survives and witnesses all the changes and tensions in the country since 2011.

The Giza Zoo is one of the biggest and oldest in the Middle East and Africa, originally built with the same standards of London Zoo in 1891. For a lot of Egyptians, it is one of the best amusement parks especially for children since it’s their only opportunity to be introduced to live animals.

The zoo receives little funding each year, making it hard to create significant developments. The funds are just enough to feed the animals and to do the most necessary improvements. The keepers there are mostly from villages and towns around the Cairo area. Some of them used to work as farmers on their land.

Most of them have been doing their jobs for many years, with some serving up to 40 years. They collect their knowledge and training by practicing, with a monthly salary of around $70 US. Many of them rely on augmenting their income by getting tips from the visitors for feeding the animals, giving information about the animals, or allowing the visitors to take pictures with the animals.

In recent years and even before the 2011 uprising, the zoo conditions are in decline. In 2004, the zoo lost its "World Associations for Zoos & Aquariums " (WAZA) membership, for failing to meet the standards and fees. After the revolution and with the economic-political crisis, it became definitely harder to look after the zoo.

In my project, I'm trying to look deeper inside the relationship between the zookeepers and the animals by portraying them together. It’s a relationship that takes years to develop. The keepers love the animals and are trying to treat them well even in very trying circumstances.

Ramzy Bensaadi

Born in 1981 in Constantine, Algeria. Lives in Oran, Algeria

Instagram: @ramzybensaadi

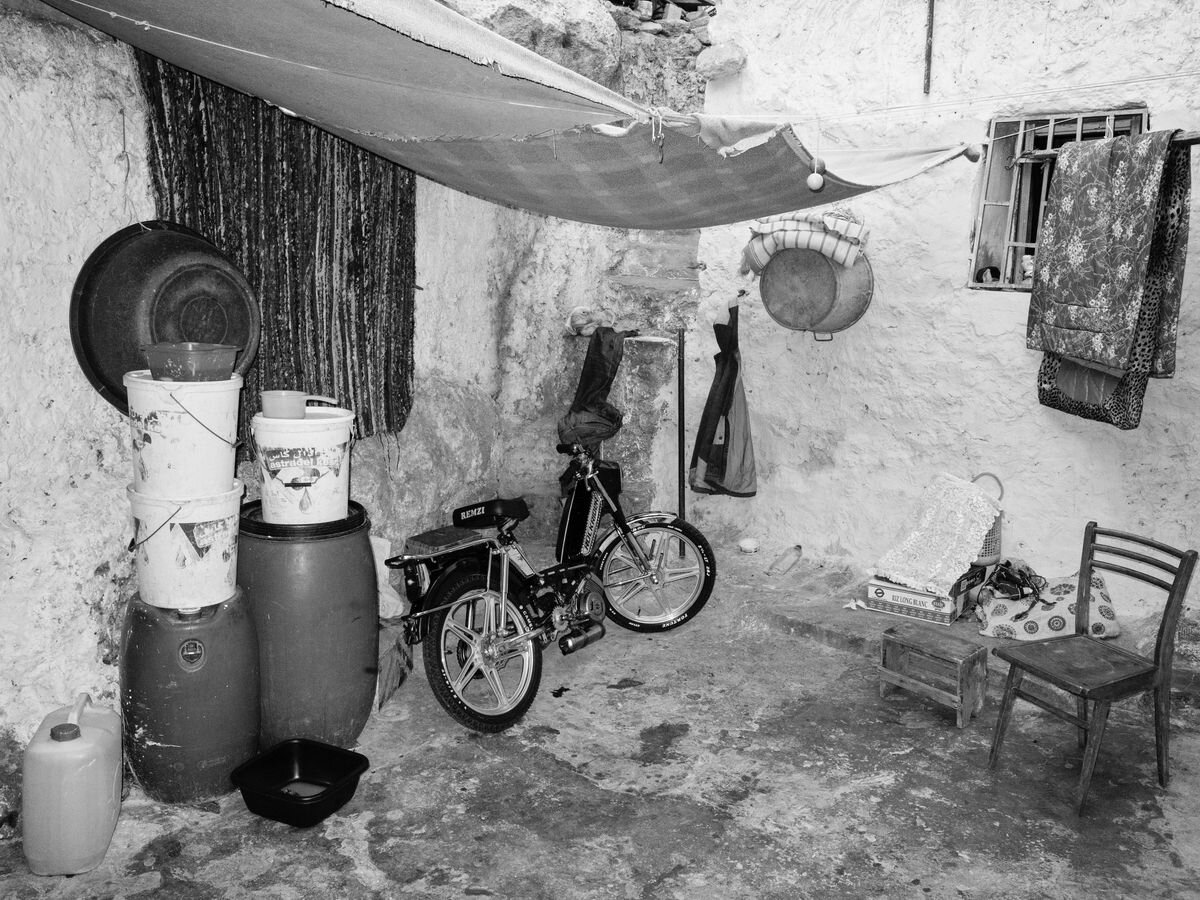

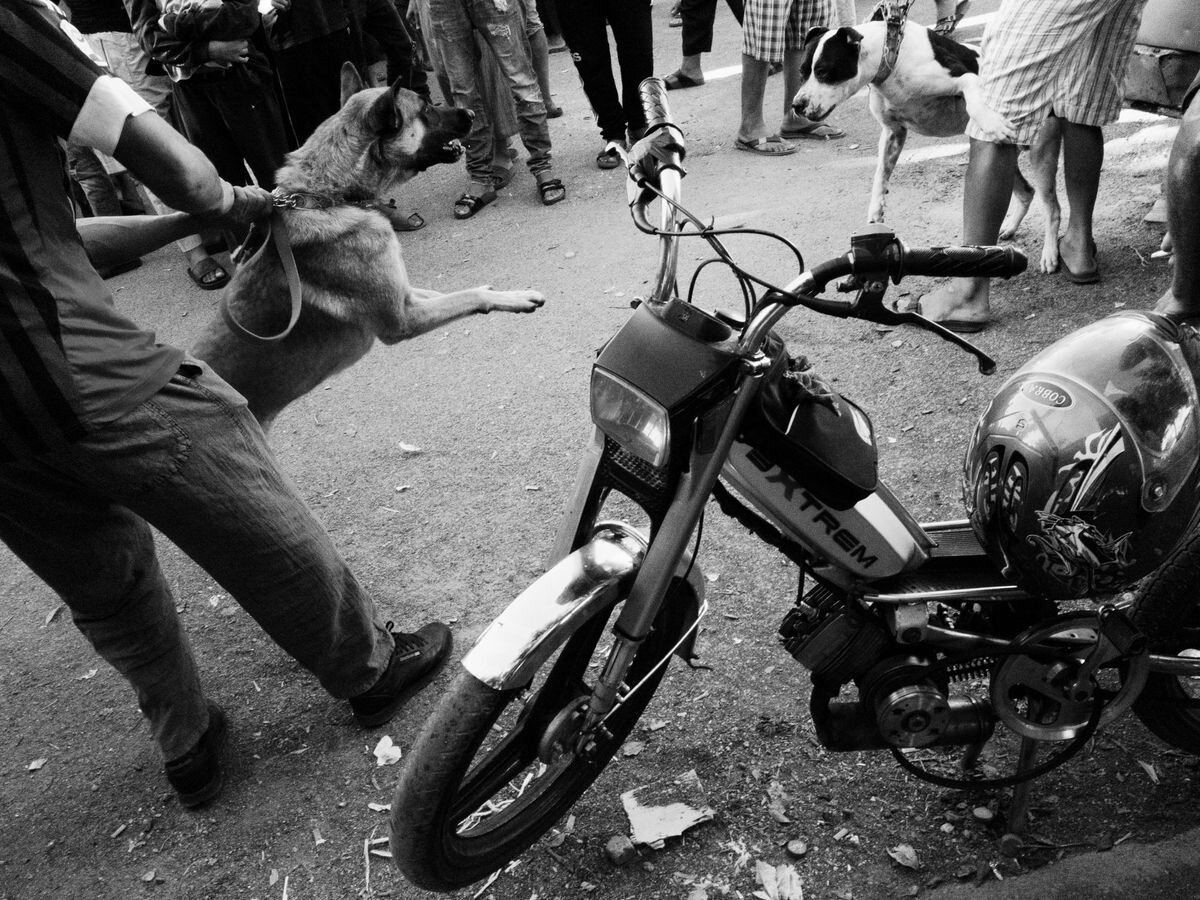

103, 2019

Friday afternoons in Oran are usually for recreation for those who can afford it but since February 22, 2019, something was added to this routine: Demonstrations calling for a political change in Algeria.

For a certain category of young people, it's race day. A race in which mopeds, that are not intended for competitive sports, are pushed to their limits on the highways. This practice, banned by the authorities for safety and security reasons, can reach speeds of 140km/hour and more. To get this number, moped racers ask friends who have cars to drive beside them and indicate their speed when they do tests on weekdays.

A race is a work in pairs: One prepares the bike so that it is efficient while another one drives it. The merit generally goes to the one who pushes to moped to the maximum.

The racers are in the majority of people with very modest or nonexistent income. They generally work without insurance. They are aware that they do not contribute to a pension despite the fact that they are not educated.

Some are quarantined and are fathers. When they are asked why they decided to have families and expose themselves to a bigger social pressure despite financial precariousness, they answer that it is their parents who insisted on it.

For them, the responsibility is a way to avoid delinquency or risky migration by small sea boats.

Mopeds can also be a means of income. A well-tuned motorcycle that has proven itself on the highways is valuable for resale, even if the secret of the success remains unattainable.

Flávio Cardoso

Born in 1987 in Luanda, Angola. Lives in Luanda, Angola

Instagram: @notflavio

Alien, 2019

I grew up on television, computers, video games and the internet while in an underdeveloped African country, feeling distanced from an African identity.

In its 45 years as a sovereign state, Angola has gone from colonization to 32 years of civil war and the rise and fall of an oil-tied economy.

Today, six years into the economic recession, its human development index remains poor. This comes in great contrast to a world where the expansion of technology and the rise of A.I. has scientists, sociologists, philosophers, and historians (e.g.: Jaron Lanier, Yuval Harari) questioning the future of the most vulnerable societies in the age of a global digital economy.

I created this work to reflect on the subject of alienation, under globalization and capitalism in modern civilization.

ALiEN is a fictional setting of a dystopic universe in which the construct of headspace with the intricate parts of man-made structures and machines are revealed to be broken.

The work is grounded in bleak aesthetics that borrow from real-life scenes followed by images of otherworldly artifacts, bringing into view the relationship between the two.

In these images are empty spaces, objects portrayed abandoned, out of place metal and concrete, and the electric power. There’s the portrayal of how discomfort and normalization of the absurd are all products of an artificial mechanism, a system that imposes itself by creating an impact on life around it.

To create this body of work, I first started by looking outwards: my surroundings, the architecture, and landscapes. From there I studied how these spaces and artifacts informed me of the social structures and aspirations while trying to understand the general driving forces of the world around me and my place in it. Finally, I looked inwards in an attempt to perceive the processes that are driving human development, from the hunter-gatherer days to the computerized Homo sapiens.

Margaret Courtney-Clarke

Born 1949 in Swakopmond, Namibia. Lives in Swakopmond, Namibia

www.margaret-courtney-clarke.com

When Tears Don't Matter, 2019

When Tears Don’t Matter unfolds as I begin a journey of healing that would take me across ten thousand kilometres of sand and bushveld, from conservancies to resettled farms, from ‘Cultural Villages’ to peri-urban squatments and so-called ‘locations’ to record the entangled relationship between self and ‘other’ in contemporary eastern Namibia.

My narrative begins under the shade of a Camelthorn tree. Men, women, children appeared from nowhere carrying chairs and plastic water bottles wrapped in wet rags … daughters leading blind mothers, wives leading blind husbands, children guiding grandparents. I came to shut out personal trauma. And I did – so warmly was I embraced by the peoples of this land on my journey -- the ǃXoon, the Nharo, the Ju/’Hoansi, !Xung, Haiǁom and the N/hoa, six out of seven Bushman ‘clans’ across Namibia who currently inhabit some of the most seared tracts of land.

What is crucial in this work is to give place to a voice in search of a listener. These photographs are not a product of a singular, dramatic news event, but rather the recording of the daily lives of those who call themselves Bushmen. A ‘shadow people’, largely invisible to the outside world, living in some of the remotest areas in the Kalahari Desert, they are currently locked into a desperate time in the history of Namibia. Their situation is born of the injustices of the past, exacerbated by the deprivations of a six-year drought, and maintained by current governmental indifference.

My aim is to connect with viewers by bringing awareness to human-ness, to stimulate debate, bring injustices to light, and to educate (where governments and press have failed). This is a social process, an ongoing relational conversation, rather than a conclusion. The journey is a demand on myself, and my viewers, to look both beyond and within oneself. It is also, hopefully, to find an antidote to despondency.

Cesar Dezfuli

Born in 1991 in Madrid, Spain. Lives in Madrid, Spain

www.cesardezfuli.com | Instagram: @dezfuli |Twitter: @dezfuli

Passengers, 2020

The ‘Passengers’ project seeks to put a face to those who have seen the need to migrate outside the system, analyzing the impact that this movement has on their identity.

On August 1, 2016, 118 people were rescued from a rubber boat drifting in the Mediterranean, 20 nautical miles off the Libyan coast. It’s one of the hundreds of boats that have been rescued from this migratory route in the past years. Only in 2016 were historical records were beaten as 181,436 migrants were rescued safe, while 4,576 died at sea.

In an attempt to put a name and face to this reality, I portrayed the 118 people who traveled on the same boat, a few minutes after their rescue. Their faces, their looks, the marks on their body, their clothes or the absence of them reflect the mood and physical state in which they were in after a long journey that had marked their lives forever.

But that would be just the beginning of this investigative project.

I soon understood that these people I had portrayed lacked real identity. They were not themselves, but they were a result of a long journey during which their identity had been diluted in the mass, sometimes hidden by themselves for fear of the environment, stolen based on abuses and humiliations. This shows that the price of traveling outside the system is too high, especially for those who pay with their lives.

During the last three years I have worked to locate the 118 passengers, today scattered throughout Europe, to understand and document their real identity, with the aim of showing that in those individuals who I had photographed in 2016, there were latent identities, which only needed a peaceful context to flourish again.

To date, I have met 63 of them, and I have located 105. They currently live in various cities in Italy, Germany, France, Spain, Belgium, Malta, Holland, and Switzerland. And, although their future is still uncertain, at least they have been able to return to being themselves.

Rahima Gambo

Born in 1986 in London, United Kingdom. Lives in Abuja, Nigeria

www.rahimagambo.com | Instagram: @rahrahhima

Tatsuniya, 2019

Lately, I’ve been thinking about filmmaker Trinh Minh-Ha’s phrase “speaking nearby” as a way to describe the visual approach of the ‘Tatsuniya’ series. The intent wasn’t to directly approach my subject to extract usable information or to affirm a position in a traditional way, but rather to turn curiosities to the things that happen around the making of these images.

The bonds and frictions between my subjects and I, the mistakes and throw away gestures made when the camera keeps recording, the invisible things learned and encountered that make no sense at that moment and do not particularly lead to a coherent end result. The residues of this energy of collective making, where lines are blurred, and visual thoughts and authorship is open-ended, ongoing and unfinished makes most of the form of in the ongoing ‘Tatsuniya’ series.

The first photographs of ‘Tatsuniya’ (2017) were about exploring the third space of collective memory, playfulness, and youth. It was an experiment with improvised prompts to weave the visual narrative together, making it something other than documentary through contestation and a pivoting away.

In ‘Tatsuniya II’ (2019), by using a workshop framework as a starting point for making the images, I wanted to explore further how to collaborate better with the students I was photographing to integrate them as participants and collaborators in the creative process.

The ensuing images created from the workshop continued with certain themes from Tatsuniya I using intuitive and improvisational strategies, referencing children’s games, lines of poetry, and exercises from a textbook called “Physical Education for Secondary School Students” as a loose framework for weaving the narrative together.

‘Tatsuniya’ is about the intangible things that happen when you bring a group of young women together and hold a space for creative expression to come through. It doesn’t find an easy point of departure from the often-cited trauma: the Boko Haram conflict that has inflicted on the young. The series is about creating a space to be present with the present, about plotting an area for playful interaction where something undefined can be stimulated.

Gianluigi Guercia

Born in 1974 in Napoli, Italy. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

www.gianluigiguercia.com | Instagram: @guerciacolour | Twitter: @GGuercia

Voortrekker 25, 2019

'Voortrekker is a road that starts from the middle of Cape Town, in a neighborhood called Salt River—a stretching snake arrives to the outskirts of the city.

It crosses different neighborhoods and areas. All of them are different: socially, racially, and economically.

There is a Voortrekker road in almost every city or village in South Africa, keeping alive the memory of the Voortrekkers that embarked in the Great Trek, a movement of Dutch-speaking settlers who searched for land they could call their own, independent of British rule in the interior of South Africa. Far from being the peaceful and God-fearing process, the Great Trek also caused a tremendous social upheaval within the region.

The Voortrekker Road in Cape Town is almost 16 km long and all its different parts become a mirror of the complexity of the city and the country. Some areas have been gentrified, others remain in decay.

The road, as with the country, is stuck between past and present, between the middle and working class, between whites and blacks, South Africans and immigrants. Photography becomes the ultimate witness of all this. It becomes a document and memory of these changes.

Gianluigi Guercia

Born in 1974 in Napoli, Italy. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

www.gianluigiguercia.com | Instagram: @guerciacolour | Twitter: @GGuercia

Alone, 2020

I’ve been living through images since I was a child. I sneaked in my parents’ bedroom and watched hundreds of movies while they were asleep. My photographs are a concise summary of cinematic images often narrating tales of solitude and bewilderment.

My pictures are a mirror of myself and the strong idea that I have about the surrounding environment, the one where I move or travel through in Cape Town. These images found me around a street corner, in a public pool, or in a hairdresser’s salon.

At this stage of my journey, I search for a more thoughtful and personal approach. Different themes and layers converge in one and unique narrative. I'm interested in a category of subjects that often represent a sort of contemporary minimalism while working on my discrete act of seeing.

A balance of shapes, lights, and subjects. In that loneliness, the possibilities of re-appropriating an innocent gaze free from the prejudicial perception of reality; not the short term appeal of an image of a sought-after anecdote are present. Faces and movements that are common but different, again, that are a reflection of myself trying to fill a void that is in all of us.

I recognize myself in the “other,” with a gaze that distances itself from any form of judgment. A loneliness that is inevitable, desperate lives looking to find meaning, a companion or a solution for that feeling.

The inspiring thoughts of Italian Photographer Luigi Ghirri resonate in my understanding and approach to the medium. He says that photography has become an opaque layer, filled with images that are superimposed on reality itself. I dig again through that opaque layer, often hunting for an image of myself.

To represent this idea, I humbly try to slow down and extrapolate images from this magmatic flow that continues to desensitize the ability of individuals to look without a preconceived approach, while trying to minimize the violence of a photographic approach that dares to understand and decode reality.

Skander Khlif

Born in 1983 in Tunis, Tunisia. Lives in Munich, Germany

www.skanderkhlif.com |Instagram: @skander_khlif

From Home With Melancholy, 2020

It is important for me to keep a deep relationship with my home country. During each of my visits, I wander the roads aiming to reconnect with the surroundings. I like playing the street photographer and trying to freeze a portion of time by catching a smile, a meditation, a dreamy or a lost look. Wondering how time has passed by and how it continues to do so.

Traveling in Tunisia long and wide, I realize through the cities and through the different environments that, while time may leave bitterness to some, it may also be synonymous with hope to others. For many, time is a friend they no longer fear. Others ask for more than it has to offer. Then there is me, coming and going and constantly returning to my memories. I remain a spectator of a time that progresses in a different way.

M'hammed Kilito

Born in 1981 in Lvov, Russia. Lives in Rabat, Morocco

www.kilito.com | Instagram: @mhammed_kilito

Portrait of a Generation: Among you, 2019

This project is a reflection on personal identity for Moroccan youth based on a selection of portraits of young people who take their destinies into their own hands.

These individuals have the courage to choose their own realities, often pushing the limits of society further. Whether it’s through their creative activities, their appearance, or their sexuality, they convey the image of a young Morocco—alert, changing, and claiming the right to be different and celebrating diversity.

These young people, whose minds embody the resistance of a palm tree—a tree adapted to the harshest Moroccan climate conditions —, defy the conservative and traditional norms of Moroccan society on a daily basis. They cultivate their private oasis despite the obstacles they encounter in a country that they feel is not progressing at the same pace as they are, and they are inspiring others along the way.

Seif Kousmate

Born in 1988 in Essaouira, Morocco. Lives in Casablanca, Morocco

www.seifkousmate.com | Instagram: @seif.kousmate

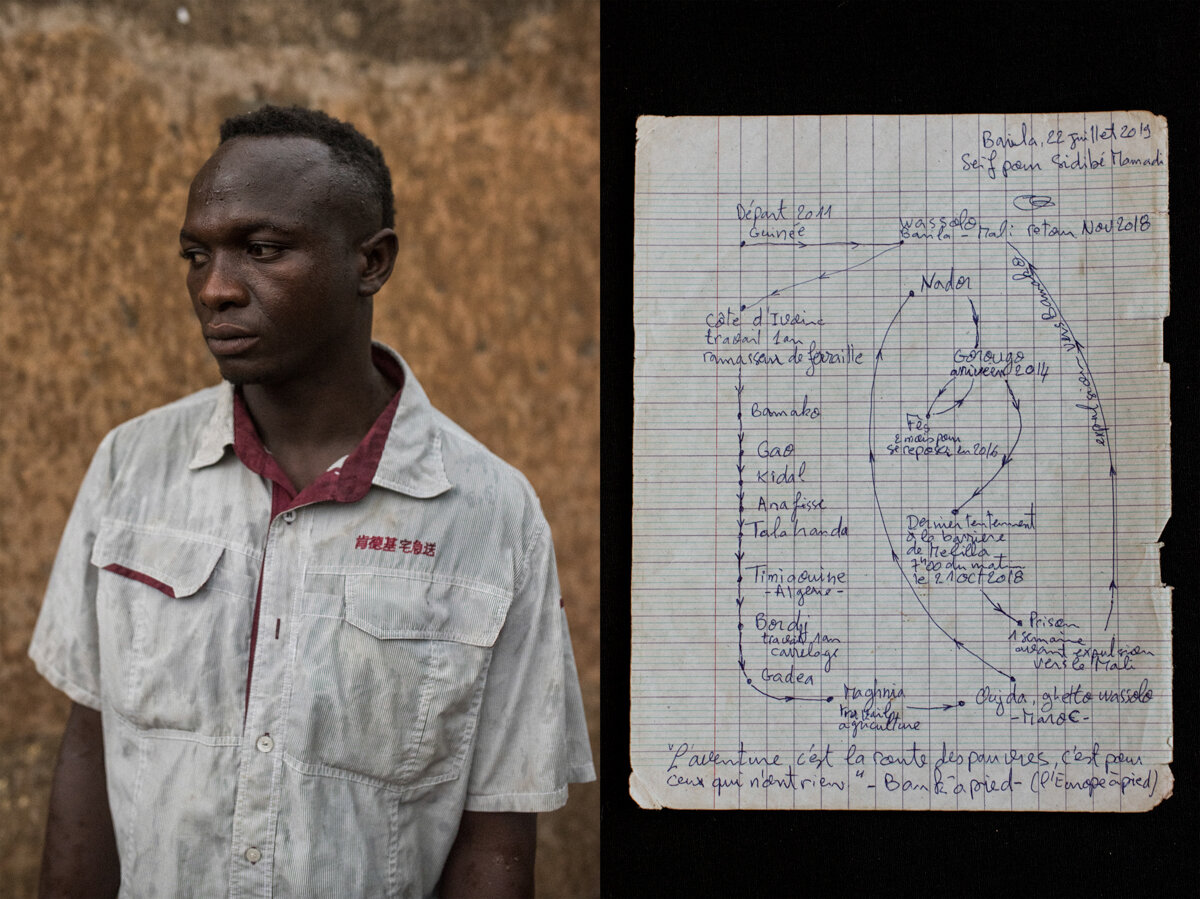

One Dream – Two Destinies, 2019

This is the story of two friends who shared the same dream: reaching Europe, where they hope to live a better life and sustain their family. Madou and Dra met in Morocco, at Mount Gourougou, the terrestrial frontier between North Africa and Europe. Both Malians have been attempting to cross the Spanish border to reach the enclave of Melilla, from which they would be able to reach the rest of Europe.

Their lives took different turns when Dra managed to climb the border wall in May 2017 and was allowed to stay in Europe while his asylum request is being processed. Stuck in Gourougou much longer than his friend, Madou is eventually arrested and deported back to his home country of Mali.

From Mali, Madou explains his disappointment and sense of failure after having been so close to reaching his dream. As he smokes joints to numb the pain, his mind is focused on getting back there at all costs. Meanwhile, Dra experiences another kind of disappointment: the realization that Europe is not a welcoming land of opportunities. His situation is nothing but precarious. He subsists by working throughout Spain as an olive or strawberry picker, depending on the season.

Nora Lorek

Born in 1992 in Giessen, Germany. Lives in Gothenburg, Sweden

www.noralorek.com | Instagram: @noralorek

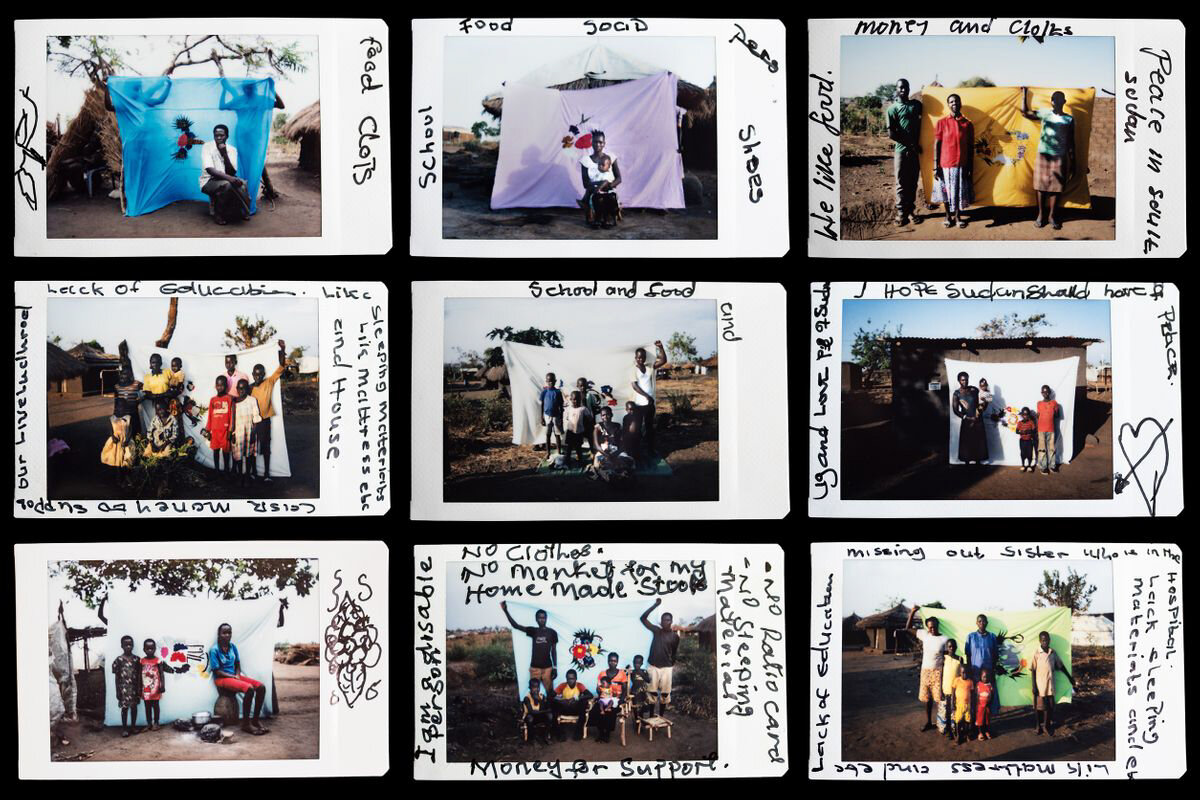

Milaya – Patters of Home, 2019

On their way from South Sudan to Uganda, refugees walked for days or weeks carrying embroidered sheets, decorated with swirls of flowers, trees, and animals. Before the war, these milayas were used for dowries and celebrations, but now, after years of violence, they are held as the refugees’ last possessions.

In August 2017 the millionth refugee from South Sudan entered Uganda to escape the war. With most of the refugees being women and children and leaving during shootings at night, their bedsheets, called milaya, are often one of the few things they carry with them. The handmade patterns have been made in South Sudan for generations and the tradition of the milayas continues in what has become their temporary home while waiting for the war to end. Bidibidi in northwestern Uganda with more than 270 000 people is considered one of the world's largest refugee settlements.

Today the women in Bidibidi continue to sew milaya. They’re hung at church on Sundays, decorate funerals and weddings, and are sold at markets in town. In these pictures the women from South Sudan are posing in front of the milayas they managed to bring while fleeing their home and the war of the world's youngest country.

Gosette Lubondo

Born in 1993 in Kinshasa, Congo. Lives in Kinshasa, Congo

Instagram: @gosettelubondo | Twitter: @GosetteLubondo

Talangai, 2017

Gosette Lubondo is a Congolese photographer and visual artist based in Kinshasa. A graduate in visual communication at the Academy of Fine Arts Kinshasa, she has been inspired since a young age by the work of her father, who is a photographer by profession.

She quickly became interested and participated in several kinois collective workshops. In 2013, she worked with photographer Bruno Budjelal. This is through a workshop organized by the collective Eza possible in Kinshasa.

Winner of the Photographic Residences of the Quai Branly Jacques Chirac Museum 2017 and Finalist of the Goethe Institut Masterclass, Lubondo has presented her work in several collective exhibitions such as Seven Hills (Kampala Biennial) 2016; Eblouissement (Biennale of Lubumbashi), 2017; Kinshasa Chronicle (International Museum of Modest Arts, France) 2018, Congo Stars, (Joanem Museum, Australia) 2018.

Lubondo's work deals with the theme of memory and the history of spaces, but also of people. She uses photography to create an intersection between the present and the past. It is also an archive of the future.

"Tala ngai" is an expression from Lingala, one of the four national languages of the Democratic Republic of Congo which means "Look at me or visit me." It is an ongoing project that started in 2017. This project is part of the theme of self-perception and what we give the outside world to see us is a way to question identity and physical appearance. It is also a way of confronting these two spaces: one intimate and the other that we judge externally. Inspired by the classical portrait and intended to be displayed in triptychs to present the women of the Kinshasa in a more realistic way by departing from how each of them has to present themselves in public in this era of the selfie. The third image is used to question the idea of classifying people in relation to their places of origin.

'Talangai’ is a work of archiving social and cultural realities of society but also a way to convey the attitude of these young women at this precise time.

Mehdy Mariouch

Born in 1986 in Casablanca, Morocco. Lives in Casablanca, Morocco

www.mehdymariouch.com | Instagram: @mehdy.mariouch | Twitter: @mehdy_mariouch

Studios, 2020

Each of us remembers those photographers who were almost smiling, where our parents took us to immortalize a celebration, an event, or simply to give us a portrait for an administrative procedure.

In these studios, often tiny, the photographer’s imagination carried us to the scenery of our desires. We reinvented so many sunsets, flower gardens, arcades, landscapes, and beaches…

We could go from one universe to another, cross the real boundaries through a process of false pretenses.

The medium is always the same. Photography transcends geographies, reinvents them. Tangier, Tetouan, Dakhla, Chaouen, or Casablanca: cities traveled through their small photo studios. One enters on the tiptoes to pick images of the past and those always present of an obsolete decor, decaying colors but witnessing an escape attempt. These fantasized worlds are becoming as much reality for the eye of the photographer as I am.

This is a world of extremes where everything becomes possible with one click. These are all borders crossed. Those agreed upon, those materials that dematerialize through the eyes. Through their pictures, these photographers I met seem to have decided to stop the time. They protect their labs like foxes defending their burrows. They maintain a classical working mode and a working frame that’s frozen, almost immutable. Either because they want it that way, or by lack of means.

These photographs, where memory is safeguarded and protected, are superabundant cocoons of inner lives unfortunately forgotten from others.

The idea of this project is to look at each photographer, in his studio, where he photographed thousands of people.

An out-of-field, out-of-time frame that adopts a seemingly disordered style, close to the kitsch; flashes, back edges, archives, and packed boxes… in the midst of all this, the photographer will, in turn, be photographed. Honoring these photographers is a tribute to photography. And it is also my vision to develop a work of memory. Because without it, our present and our future would be meaningless.

Mehdy Mariouch

Born in 1986 in Casablanca, Morocco. Lives in Casablanca, Morocco

www.mehdymariouch.com | Instagram: @mehdy.mariouch | Twitter: @mehdy_mariouch

Hammam diaries, 2020

‘Hammam Diaries’ by Mehdy Mariouch is a trip back in time. The artist dives back into escaped, hardly forgotten, and hidden childhood souvenirs, or memories through his exceptional, unique, and powerfully emotional photographs.

The bath benches: those magical places where pale and evanescent shadows cross through an expanding vape that covers each corner of the place. It is where water is streaming as usual and where various silhouettes pass through all day long.

The images immerse us in an intimate world within a public space where social gatherings, meetings or encounters happen. It is usually where opposite feelings and emotions merge and mingle such as relaxation and tiredness, happiness and sadness, nostalgia and joy, melancholy and euphoria.

The project is an integral part of a series of photographic projects about memory and abandonment. ‘Hammam Diaries’ represents a challenge to the artist.

Mehdy Mariouch shares his sociological perspective and works on a documentary by using his camera to capture some intimate moments of naked or half-naked people in Hammam and also moments of cultural transmission and sociological inheritance.

Frédéric Noy

Born in 1965 in Beauvais, France. Lives in NurSultan, Kazakhstan

www.fredericnoy.com | Instagram: @fredericnoy | Twitter: @fuddish

Lake Victoria slowly dying, 2019

"In the next 50 years, if nothing radical is done, Lake Victoria will be dead because of what we are pouring into it," said Professor Nyong'o, Kenyan Governor of Kisumu Province in February 2018.

The hazardous prophecy concerns the 68,800 km2 inland sea, the largest freshwater fishing pond of the planet. It’s an ecological pole, economic prime mover, a natural reservoir that 30 to 50 millions Tanzanian, Ugandan, and Kenyans depend on directly or indirectly, nearly fifty-percent of them live on less than $1.25 a day.

Yet the East Africa giant is in a phase of imperceptible agony. Global warming affects the fish and water levels. The super-storms that once happened every 15 years is now an annual occurrence. Overfishing and poaching accentuate the decline in number and size of catches. The militarization of the protection of fishing areas undermines the fisheries sector that is of major economic and social importance. The growth of the water hyacinth immobilizes the boats. The mining of banks whose sand is harvested to be sold destroys the topography. Industrialized coastal cities discharge their wastewater. Population growth and rural exodus erode wetlands, reducing the natural filter that is used to purify runoff water. As a morbid touch, fishing communities have an HIV prevalence rate three times higher than the general population.

Social decommissioning creates poverty which unconsciously entitles anyone to destroy the environment. A vicious circle where every need for survival or desire for profit engenders a new injury. Everyone perceives that times have changed without really understanding the implication.

In the past, the giant was stronger than the local residents. Now everyone nibbles a portion of the flesh of the lake, daily. How to blame the trimmers of East African economic growth? Between living or preserving the natural cycle of the lake, which belongs to no one but also belongs to everyone, the choice is quickly made, in the ignorance of the true cost.

Lee-Ann Olwage

Born in 1986 in Durban, South Africa. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

www.leeannolwage.com | Instagram: @leeannolwage

The Dance, 2019

On the night of the matric dance (prom night), communities on the outskirts of Cape Town are buzzing with activity. Red carpets are rolled out while aunties decorate houses with organza fabric and tables are heavily laid with food for the family (including everyone from your auntie to your auntie’s auntie) and friends to share.

The street outside is filled with family, friends, and community members. Excited kids run up and down the street as the sound of a sports car fills the air as it approaches the crowded house. A young woman, wearing a ball gown that reminds you of a Disney princess, steps onto the red carpet and the community cheers with pride. Her date, who is anxiously waiting with a bunch of flowers, is wearing a beautifully tailored tuxedo that is perfectly color-coded to match her dress and complemented with the latest pair of sneakers as the perfect cool accessory.

For one night they get to look like movie stars and are treated like royalty by their family. It’s only when you take a step back from the glamorous scene that you notice the stark contrast of the gritty environment that creates the background for the celebration. You begin to get a glimpse of the many challenges these students have had to overcome in order to finish high school.

For months leading up to the matric dance families who live in poverty-stricken areas save up to buy extravagant ball gowns, tuxedos, and limousines to celebrate the big night. If a family is lucky enough to have a student graduate from high school no effort is spared to give them the night of their dreams. This is because for most families this might be the first family member to graduate from high school. It’s a big achievement in communities where only around thirty to fifty percent of students manage to finish high school. For previous generations, the percentage was significantly less.

As a photographer, I’m interested in using the medium as a mode of celebration and this project serves as a celebration of these students.

Lee-Ann Olwage

Born in 1986 in Durban, South Africa. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

www.leeannolwage.com | Instagram: @leeannolwage

#blackdragmagic, 2019

The project ‘#blackdragmagic’ was created in collaboration with drag artist and activist Belinda Qaqamba Fassie and tells the stories of black queer, gender-nonconforming, and trans bodies who grew up and navigate their daily lives in the townships of Cape Town.

The project is about augmenting the power in these stories of the daily township, exploring spatial navigation, migration, culture-, gender- and sexual- identity. The collaborative project was created to serve as a platform of expression for black queer bodies where they were invited to co-create images that they felt told their stories in a way that is affirming and celebratory.

The project was shot in Khayelitsha, a partially informal township in Western Cape, South Africa, located on the Cape Flats in Cape Town. It is reputed to be the largest and fastest-growing township in South Africa. The name is Xhosa for Our New Home. And for the subjects of ‘#blackdragmagic,’ the township is home and is the space where they navigate their daily lives.

But in reality, the township is also the space where they are subjected to harassment, violence, and discrimination on a daily basis. The process of creating the project became a radical and progressive act of activism to reclaim the township and to stand up against the overwhelming climate of discrimination black queer bodies face.

Onwumere Chukwudi

Born in 1989 in Imo State, Nigeria. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

Instagram: @chuckz_zi

Road Runners, 2020

The street is often associated with violence, but in these same streets lie aesthetics and the beauty of hard work and perseverance. And one of such beauty I have chosen to identify with is this project. I have looked, wondered, puzzled and admired every scream, every run, every smile, every devotion that I see on display.

I chose to focus my art on this set of people because they are part of our everyday life and can be identified almost everywhere in Africa. Street hawking is one of the sources of livelihood for many young uneducated Nigerians who come from less privileged backgrounds.

I see them every day on the street, when I travel, when I take thoughtful walks or when I’m going about my day documenting the beauty the environment owns. I see them on the streets with true work and countless jugs.

They are runners…

With speed like that of a power-bike

They are hustlers…

Their drive, unwavering

They carry their wares like a mother does her child

They roam in troops like soldiers on the path of war.

They are neither deterred by the scorching sun by day nor the darkness that looms at night.

They are my streets impossible, the unseen beauty.

Gloria Oyarzabal

Born in 1971 in London, United Kingdom. Lives in Madrid, Spain

www.gloriaoyarzabal.com | Instagram: @gloria_oyarzabal

Woman Go No’gree, 2019

Empires, by their nature, embody differences, both between metropolis/colony and colonial subjects. Imperial imagery floods popular culture. During European colonialism gender categories were institutionalized in many African cultures as one kind of bio-logic "new tradition."

Can we assume social relations in all societies are organized around biological sexual differences? The infantilization of women as part of the Western patriarchal system was also exported with the colonization of the mind, executed in the name of morality and values, configured a state of vulnerability, and thus making a propitious dependency path.

Beauty circulates as a form of a commodity with social, economic, and cultural value. However, these norms are often measured with Eurocentric values, white beauty narratives (thinness, youth) being strongly racialized.

Whiteness is reinforced as the norm, "otherness" becomes fetish or "exotic." The three central concept pillars of Western feminism—women, gender, sisterhood—are only understood with careful attention to the patriarchal nuclear family from which they have emerged, a familiar form that’s far from being universal.

We should take into account issues like class, race, age, gender, even health, as being fundamental to the female experience. Eroticism, sexuality, sisterhood, motherhood, marriage, tradition, domestication: All these aspects and nuances, with its own lights and shades in each society, should come out in the same level so we can compare them.

Many racialized feminists believe that mainstream feminism has acted as another invisible ballast on their backs, showing itself traditionally paternalistic and exclusive from other realities that don’t fit Western model, adopting it as a universal mantra, setting an agenda that doesn’t correspond to the concerns of the non-white world but speaking for the rest of the women of the planet.

African social networks also boil with current debates, such as that of gender roles, which is structured around women who avoid the label of "feminist" understood as Western women do. Maybe by understanding history we’ll be able to overcome social and symbolic ascription.

Let us wish for new ways of relating genders, of new models of intercultural dialogues not based on supremacy nor on an excluding hierarchy. Maybe then identities, both individual and community, could naturally develop towards a society in which one wouldn't have to be invisible in order to advance. Decolonize feminism by questioning the Eurocentric frameworks that construct gender categories in a universal manner.

Lynn

Born in 1986 in Alger, Algeria. Lives in Pantin, France

www.lynnsk.fr | Instagram: @lynnnsk

Rue Belouizdad, Alger, 2019

I was born in Algeria in December 1986. I lived there until I was seven. Because of the civil war, my parents and I moved to France. In the following years, we came back there for the holidays, until I was 10. Then my parents stopped bringing me with them. For a long time, memories came back to me like old dreams. Memories of Boumerdes, the city of my childhood, and the « Champ Manoeuvre » district, in Alger.

However, it took some time for the mental process to turn into a geographical path. In October 2014, I went back to Algeria for the first time after being away for 17 years.

In Alger, I stayed at « rue Belouizdad », in a popular district, with my aunts, H. & N. Since their sister got very sick two years before, they moved in her flat and never left it when she passed away. B., the nurse, didn't want to return to her family's home, and she also stayed in the flat.

This photographic series takes place in this little apartment that is shared by four women. N., who is retired, and H. who is on long-term sick leave. H. and N. spend a large part of their time looking out the window over to the « Premier Mai » square, smoking cigarettes, and sleeping, as if to rest from a country that has mistreated them, whether it is by its "hogra,"* or by its "dark decade," leaving scars that are barely just healing. And then there is B., who takes care of everything and who, when she is not praying, is always willing to prepare my favorite dishes.

I’m connecting back to my memories, in this world that appears to me strange and familiar at the same time. I’m trying to create images through the filter of my mental pictures. After these years of absence, I’m trying to deal with what can’t be forgotten anymore.

*Hogra: an Algerian word has no direct semantic equivalent in English and can be translated as contempt, injustice, or oppression

Ugo Woatzi

Born in 1991 in France. Lives in Brussels, Belgium

www.ugowoatzi.com | Instagram: @ugowoatzi

Chameleon, 2019

Having grown up in a patriarchal and traditional village in the south of France, I had to follow certain codes and rules in order to become “a man.” I couldn’t embrace my identity freely, hiding and performing for myself most of the time. Closeted, alone, and living a secret life for many years, I was scared to be judged by my sexuality.

It is in Johannesburg, South Africa where I found myself being welcomed and surrounded by an incredible queer creative community, and where I began to understand that I could express myself through photography. After I ended my program at the Market Photo Workshop, I began to create the series ‘Chameleon’ in 2016.

Three years later, I returned to Johannesburg to further develop this body of work, its title reflecting so many of the experiences of existing and creating between these two vastly different contexts.

‘Chameleon’ is a photographic series about hiding and revealing. This duality shares the metaphor of the little lizard that hides in plain sight. It is a narrative exploring masculinities and spaces beside the heteronormative structure. The still frame evokes the love, hope, and fear of people who exist outside these constructs that can be suffocating. I create my images through evocations of the personal and collective experiences of my community. By using masks, fabrics, accessories, and composing with colors, shapes, shadows; I question the performative / camouflage aspects of our lives.

My images are staged to create visual metaphors and specific statements which form part of a global visual and political activism. I am equally engaged in celebrating as well as illustrating the diversity of masculinities.

This camouflage ability is an expression of how I seek to open up a dialogue about those of us who live but do not fit the conventional molds constructed by heteronormativity. The series is confronting our societies in a time when LGBTQ+ rights are under attack in many different places in the world. My work aims to encourage queer people to show themselves and be proud of who they are.

Ismail Zaidy

Born in 1997 in Marrakesh, Morocco. Lives Marrakesh, Morocco

Instagram: @l4artiste | Twitter: @l4artiste

العائلة family, 2019

Photography is a family affair for me. In 2018, I started a project named '3aila'( عائلة), which means “family” in Arabic. My younger brother Othmane (19 yo) and my sister Fatima (16 yo) play a huge part in developing the ideas behind the pictures. All of my pictures are taken on my phone (Samsung Galaxy S5), in Studio Sa3ada, a space that we created on the rooftop of the building we live in. Sa3ada means “joy,” which is the feeling we get while creating in this space.

My creative process starts with finding ideas and getting props from the flea markets and setting everything that I need. It also depends on my siblings finding time between their school schedule, sometimes everything is put on hold when they have exams.

Family is a big part of my life, I rely on them a lot, and I'm trying to shed light on this subject: the problems, the lack of communication, the distance between siblings and their parents. Family estrangement is a problem that affects many but is rarely talked about, I am trying to treat this issue throughout my work, showing that family is one of the most valuable gifts in our lives.

Fares Zaitoon

Born in 1990 in Cairo, Egypt. Lives in Cairo, Egypt

www.fareszaitoon.com |Instagram: @fariszaitoon

The Return of the Prodigal Son, 2019

“For this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found” [Luke 24:15]

A divine verse told many years ago, but our days are no longer divine, and miracles no longer happen.

I am not sure if I was dead and was revived, or if I’m somewhere in between.

I created my own path, far from my father’s; from the terror haunting my dreams, seeping into my waking life, to the point where I couldn't tell what’s real from what’s not.

Being 50 years older, communication and acceptance of my ideas conflicted between both of us, perpetually difficult.

Drugs were my only refuge. The only way I could see myself without my fearful gaze, or yours.

Drugs are both poison and honey, but only one of them back then. I don’t know if he was aware of that then. Didn’t you care that I made my own choices? That I defied yours?

I found myself losing everything, bit by bit, and my world was suddenly flipped over its head. Everyone around me was either on the verge of death or trapped within its chains. And I, too, was on the brink of my ruin.

I became a little kid again, reaching out for someone to pull me out of my own hell.

I ran away, trying to find shore, even though I knew no one would be waiting on the other side. After all these years, after what I’d become, I knew no one would accept me.

But the truth was far from that.

My loneliness dissipated. I found my father by my side. We had forgiven each other and finally tried to communicate.

It’s been five years. I can still remember it all vividly, and I realize that some things will never change.

I still find myself going back to old habits, I still find fractures in our relationship. I still don’t know who is to blame, or who’s at fault.

All I know is I’m still searching for myself, despite everything that happened and everything that will.