CAP Prize 2017 | Short List

CAP Prize 2017 | Short List

The following 25 artists were selected by the CAP Prize panel of judges comprising 20 international curators, editors, publishers, and artists, from hundreds of applications for the CAP Prize 2017. Five of them have the chance to be awarded the sixth Prize for Contemporary African Photography to be announced in June 2017.

Mohamed Altoum

Born in Khartoum, Sudan. Lives in Nairobi, Kenya

www.mohamedaltoum.com

Sudanese cinema - long years of solitude

Cinema has a great role in the whole world it reaches nations with a simple, universal language and without complication, through it ideas and problems that exists on society can be changes, it is the easiest way to enter the conscience of a person and give them new ideas, wither they are educated or uneducated. If cinema is utilized in on a proper way we will see a conscious and open mind/ advanced generation Cinema in Sudan faces big problems, it's role on a cultural level is completely absent, and and it is not as present as it use to be back in the 80s, where it struggled but despite of that it still produced works that deserve respect.

Emmanuelle Andrianjafy

Born in Antananarivo, Madagascar. Lives in Dakar, Senegal

Nothing's in Vain, 2014–2016

Life is unpredictable and I had never imagined I would live in Dakar, capital of Senegal, one day. I left my home country Madagascar in 2000 to attend university and work in France. In 2011, I moved to Senegal to follow my husband. Maybe a bit naively I thought returning to the african continent, though to a different region, would not require much adjustment. I found myself totally disoriented by my new environment, the different reality and energies. For me, it was an exhausting place to negotiate and the temptation to escape it was great. Instead, I decided to confront Dakar by walking its streets and entering its homes. My intention was simply to immerse myself in this environment, hoping it would help me process the city, make sense of it and address the questions it raised. After 2 years of observation and wandering, I haven’t found many answers. I don’t think I will, but throughout the process I have come to accept the state of things. I don’t think there is anything I can say or do except for that. My project is intended as a visual poetic commentary on life.

Miia Autio

Born in Reisjärvi, Finlad. Lives in Helsinki, Finland.

www.miiaautio.com

Variation of White, 2015/2016

Variation of White deals with the subjective nature of the gaze, facing diversity and prejudices, and the portrayal of otherness. The photographs portray a minority, people with albinism in Tanzania, who suffers from myths surrounding their appearance and discrimination based on them. The work includes a documentary film "Miss Albino". The photographs are negative images of the originals. With the first glance they adhere to the viewers’ preconceptions of the subjects’ appearance, which makes them disregard the logic of the inverted image. The truth is revealed only after closer examination, but the original image is also viewable through an optical illusion. Reflection of the original image can be seen by looking at the red dot for 30 seconds and after that turning the view simultaneously blinking to a white surface. This illusion, a negative after image, is created when the brain is too slow to interpret the information provided by the eyes.

Equally time and closer examination can change our personal prejudices. Variation of White strives to get the viewers to question the way they construct their own reality. What we see is never a direct representation of the external reality but is always born through the synergy of our vision and mind. The subjectivity of our gaze is revealed when an image first perceived as reality is revealed as something else.

Javier Corso

Born in Barcelona, Spain. Lives in Barcelona, Spain

www.javiercorso.com

Essence du Bénin, 2015

In Benin, a country in the Gulf of Guinea bordering Nigeria, a vast network of illegal trafficking of petrol from Nigeria exists. Benin does not have enough petrol stations to cover the population and also cannot compete with Nigerian petrol prices. From this need emerged a lucrative business opportunity. A few decades ago, Beninese traffickers started to buy petrol in Nigeria, where it is much cheaper because Nigeria is the leading producer of petrol in Africa. They then started to sell it in roadside stalls around the entire country, at a price lower than it is in the petrol stations.

Over the last few decades, the trafficking bosses have reached a lot of power in Benin. Politicians have surrendered to them and the police turn a blind eye in exchange for a few CFA (the Beninese currency). Many women, people with disabilities, university students and even children depend on this activity. All of them are exposed to the harmful gases that petrol emits and to the danger of explosions that can be caused by small accidents that happen while transporting the petrol. These have caused hundreds of deaths in recent years. The streets of Porto Novo, the capital, are full of traffickers who transport drums of petrol by motorbike. They are commonly known as “human bombs”, because they often have accidents when the petrol they transport explodes.

Traffickers distribute the petrol amongst their customers throughout the country. It is an extremely well-organised business within the Association des Importateurs Transportateurs et des Produits Revendeurs Petroliers (AITRPP), which is a legally registered association. Joseph Midodjoho, popularly known as Oloyé, is the president of AITRPP and is actively involved in politics. Under him, there are representatives for the twelve departments of Benin who control seventy seven regions. On the bottom level there are presidents of the districts, neighbourhoods and towns and the street stall sellers.

In Benin, there is also high unemployment and it is hard for people to find good jobs. This business generates billions of CFA each year for the Beninese traffickers, and none of this money goes to the Government.

Karim El Maktafi

Born in Desenzano del Garda, Italy. Lives in Brescia, Italy

www.karimelmaktafi.com

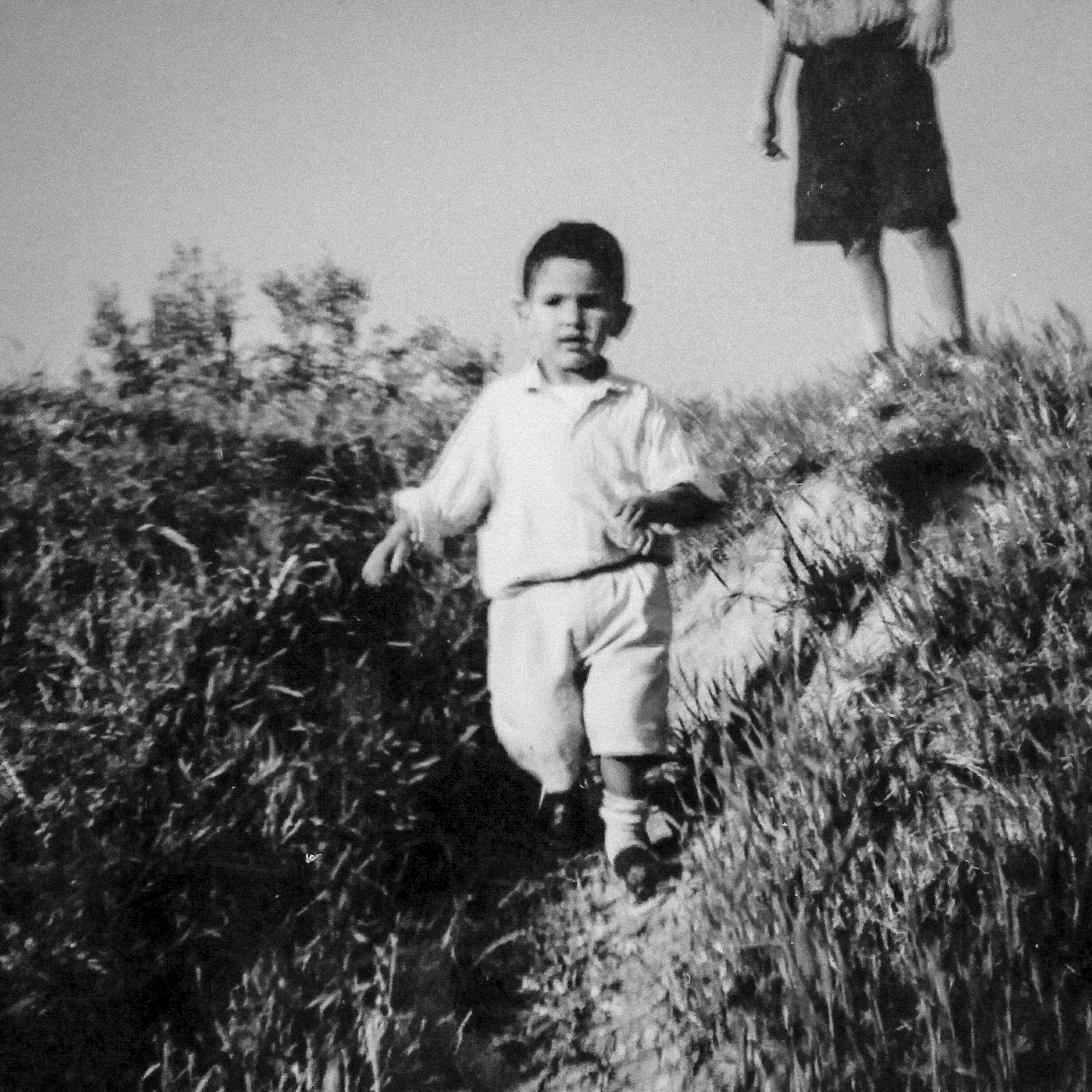

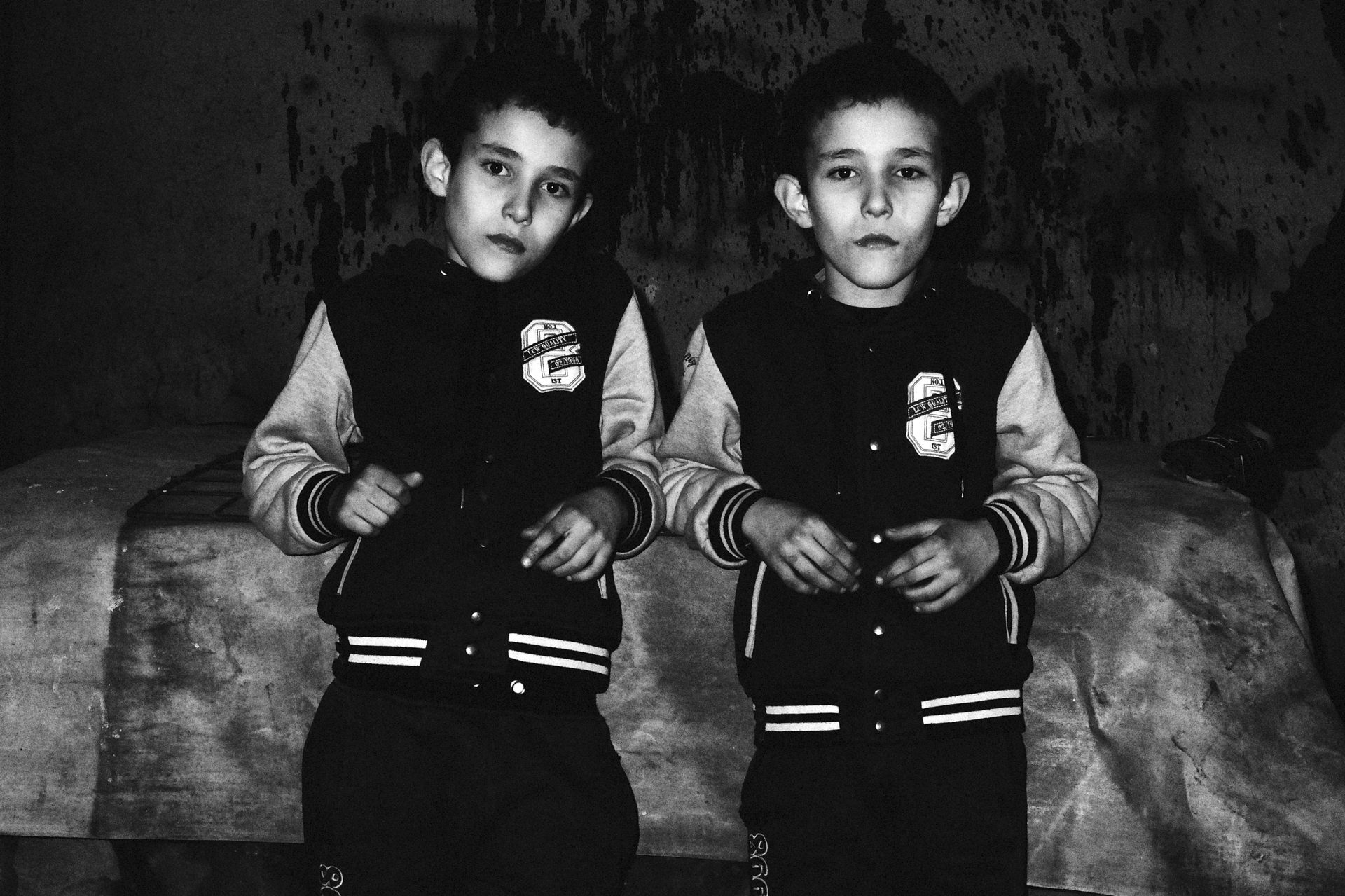

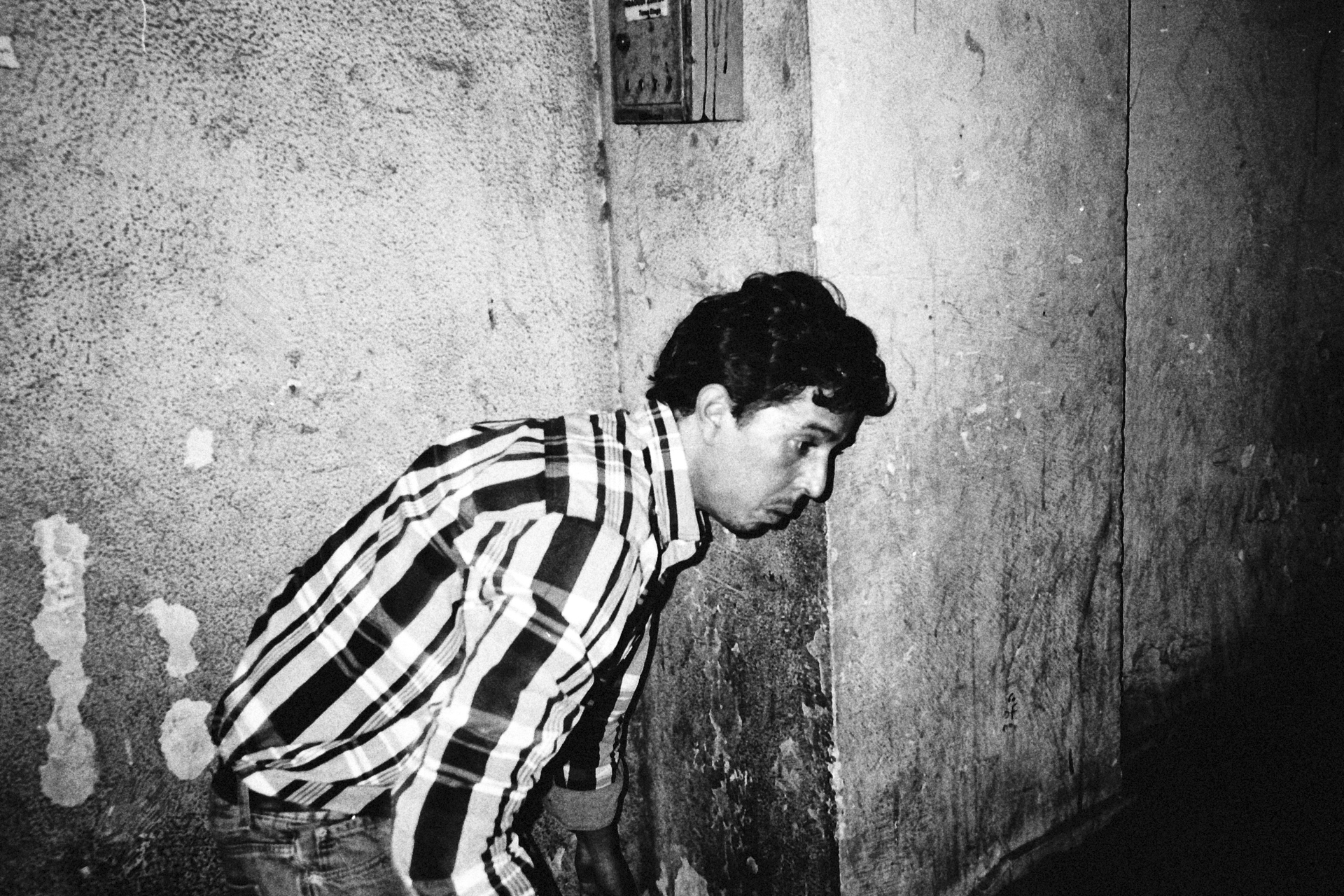

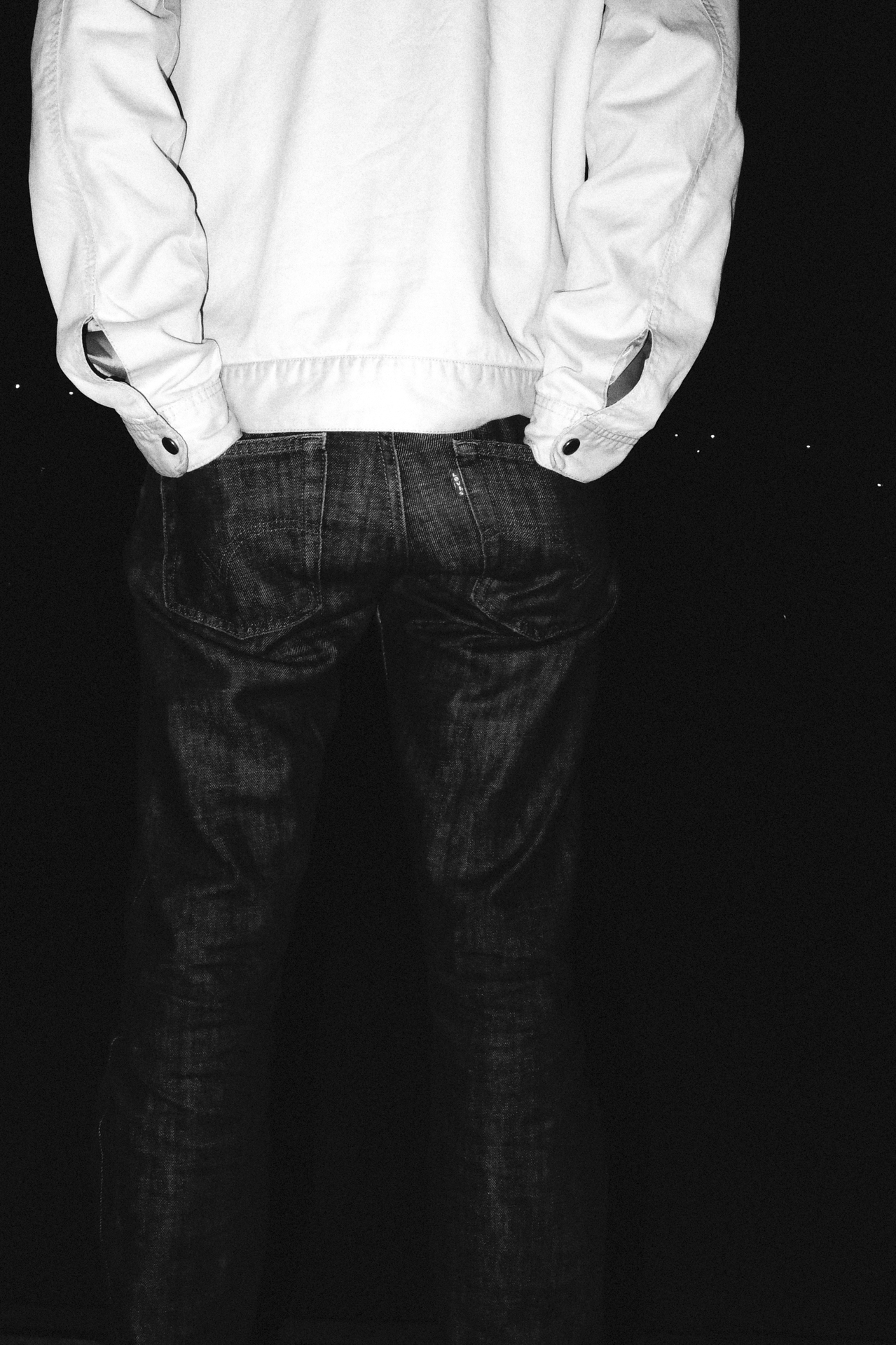

Hayati, 2016

Hayati (“my life” in Arabic) is a visual journal realised exclusively with a smartphone. Hayati reflects and investigates on the identities of “second generations”. These children of immigrants, born and raised in Italy, balance between two realities that at first sight might seem incompatible.

To produce this investigation, I became both its subject and its object. I was born in Desenzano del Garda, a village near Brescia, Italy, from Moroccan parents. Growing up between two worlds forced me to sharpen my gaze and to compare these perspectives which often diverge from each other.

Embracing a single identity is not easy; feeling out of place or like an odd cultural hybrid often happens. Yet, while trying to define this identity, one understands the privilege of “standing on a doorstep” at the edge of two environments.

One can decide who to be, where to belong, or to create new ties, while keeping alive the experiences learnt along the path. One must learn to juggle multiple languages, cultural taboos, references, prohibitions, and learn to teach those who are not also standing on the doorstep.

I had to travel inside my own life and family. I faced doubts, hesitations and afterthoughts, but I realised an honest portrait of how I have lived until today.

The most interesting aspect of this story - of my story - is the creation of a less restricted reality. One that is undefined, in which various beliefs and experiences thrive and form a unique harmony.

This project was realized in Italy and Morocco and also incorporates archive images from old family albums.

Rahima Gambo

Born in London, United Kingdom. Lives in Abuja, Nigeria

www.rahimagambo.com

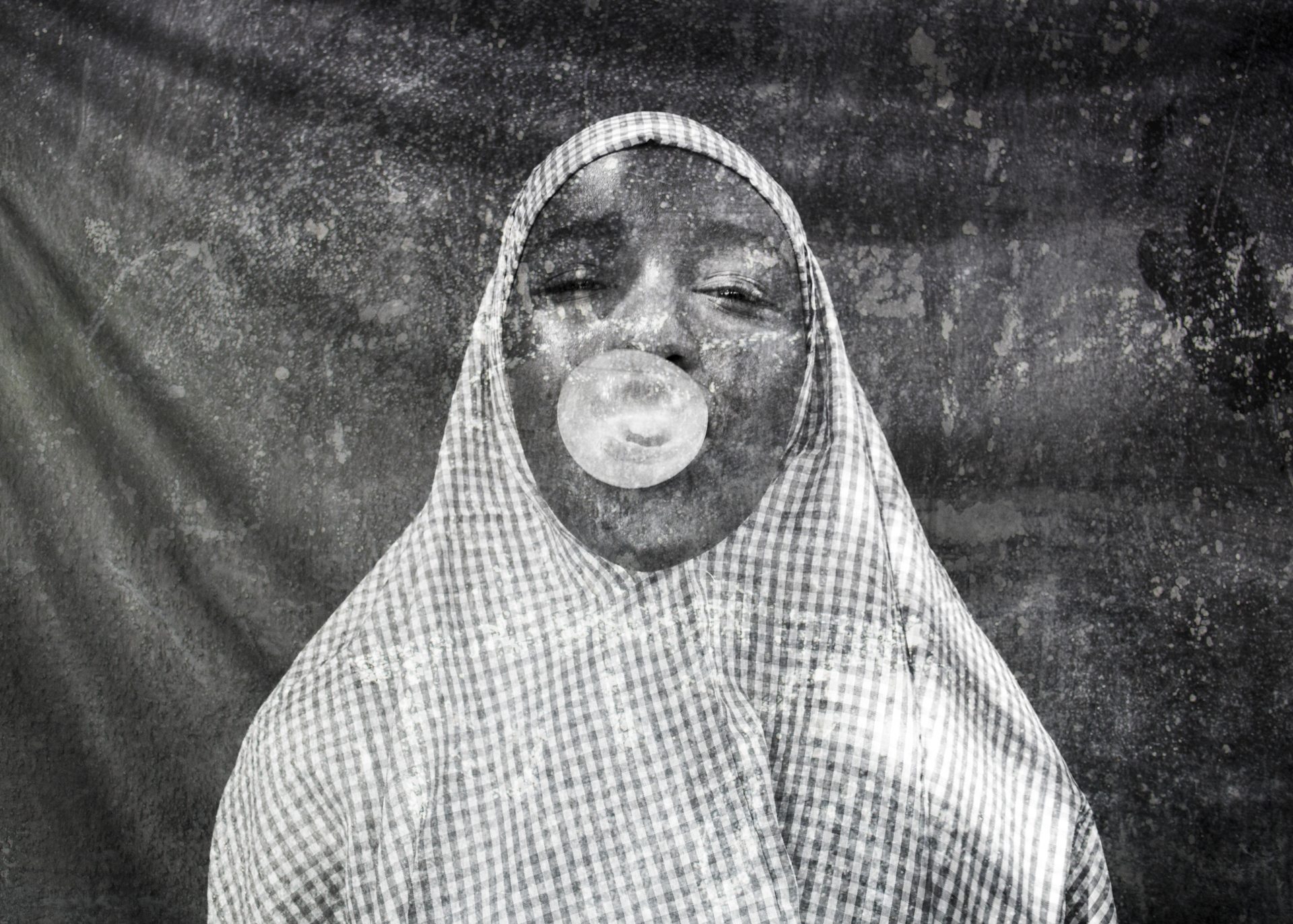

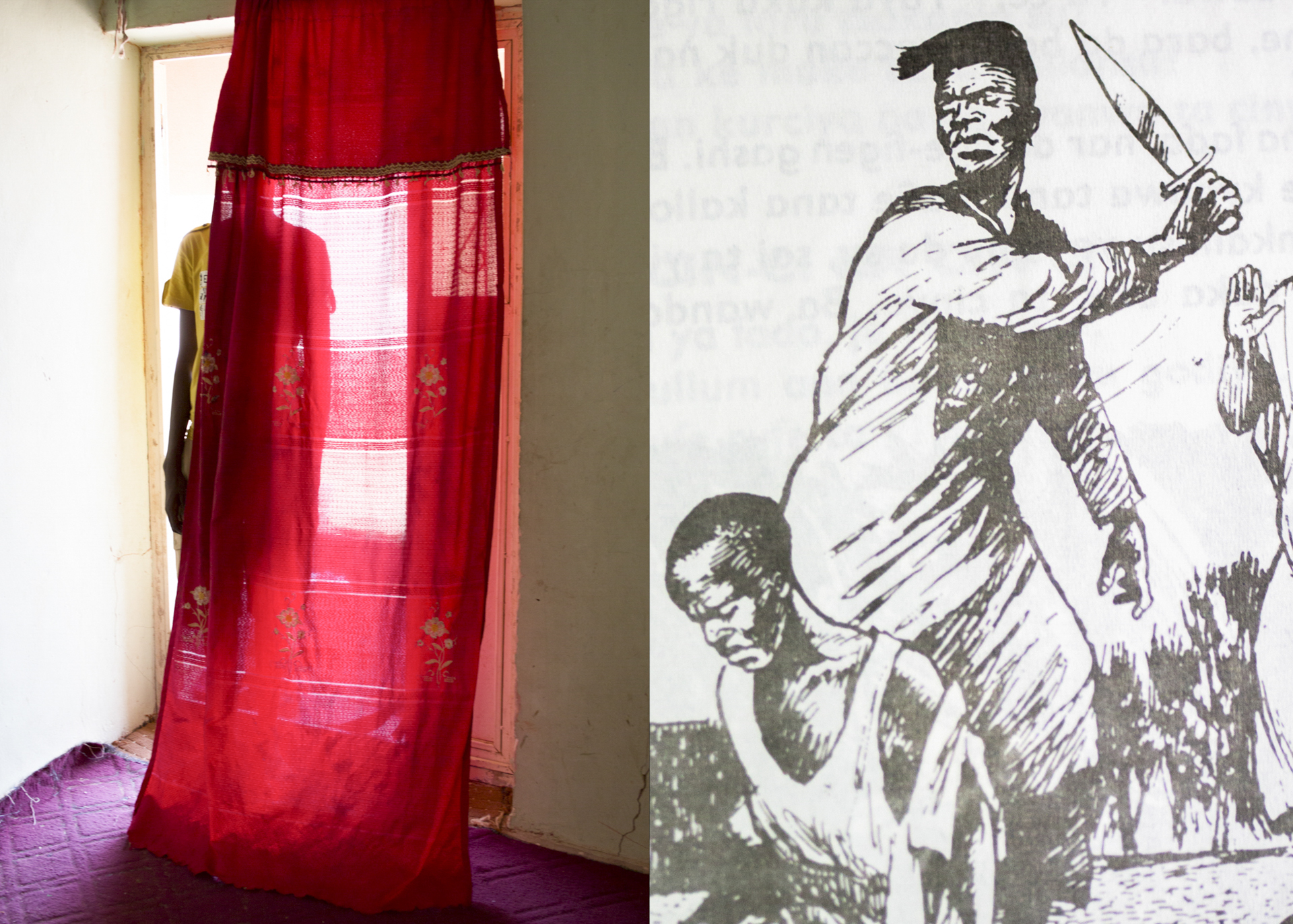

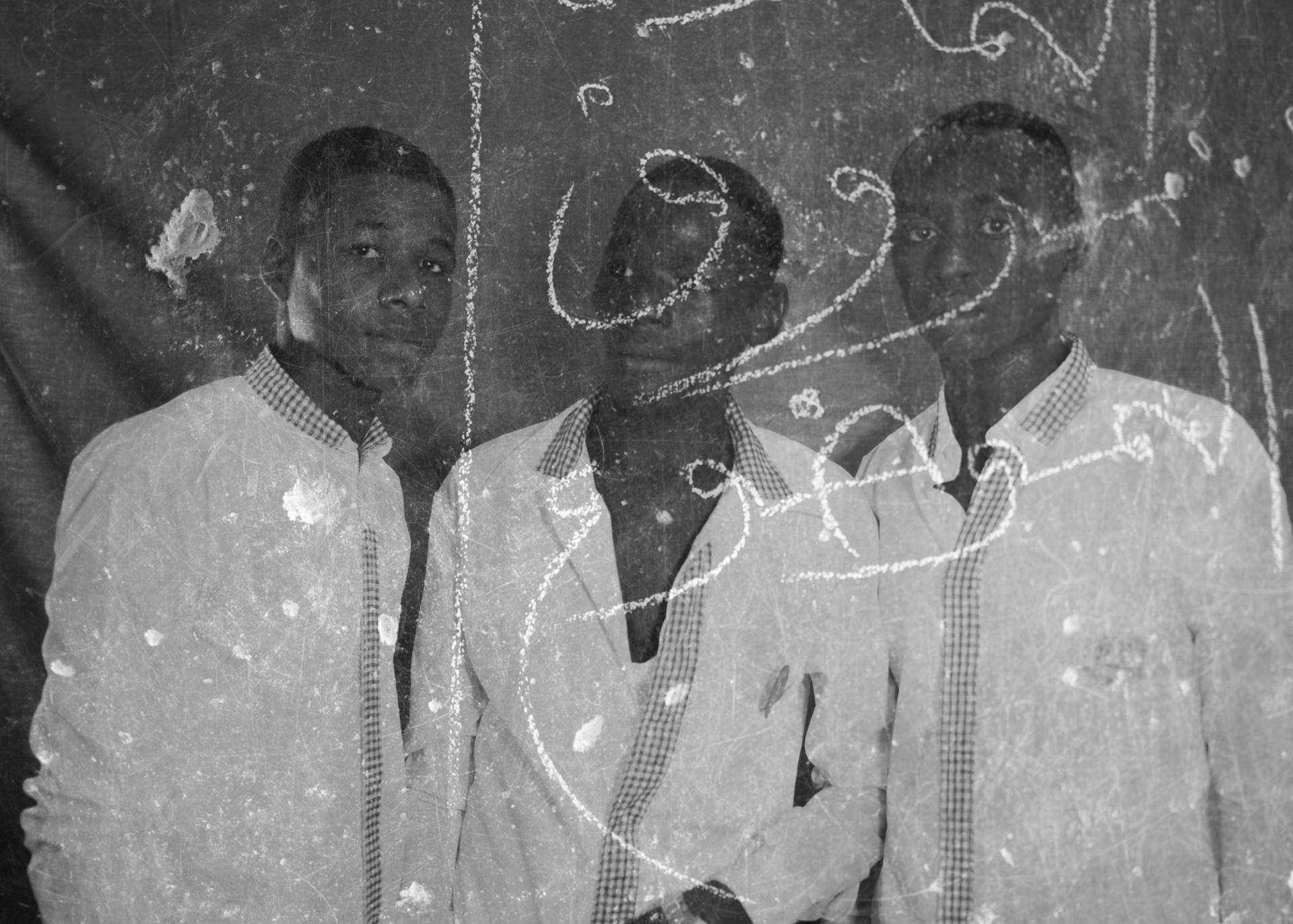

Education is Forbidden, 2015-2016

I began the “Education is Forbidden” project with a need to understand what it means to be a student living in the midst of the Boko Haram conflict in north eastern Nigeria.

“Boko Haram,” which loosely translates to “Western education is forbidden,” began an insurgency in the region in 2009 with the aim of creating an Islamic state purged from all Western influence, especially secular education.

The insurgents have directly targeted schools, universities, teachers and students with thousands of students abducted, displaced and killed by the group.

This series of images bring the focus back to the individuals most affected by this crisis, secondary school students in Borno State, the epicentre of the conflict. As the educational system has been altered into a dystopic nightmare by the conflict, these student’s narratives and individual complexity have been obscured by the often vague, violent and sensational media coming from the region.

The photographs attempt to permeate through this veil of generality to suggest an emotional complexity to these teenagers, who have often been described as powerless victims.

There was a schism in the way students were described in books and media and the current reality in which I encountered them. The use of illustrations from Nigerian school books in the diptychs and the double exposures seen here highlight this tension, pointing to a multi-layered ambiguous truth of who these students are. This abstract approach to the subject revealed themes of transience, memory, history and trauma that became reoccurring motifs in the project.

A pock marked blackboard exposed over a portrait of a school girl, can begin to communicate a lingering trauma and infrastructural decay that began decades before, but is now ultimately destabilised by conflict.

Schools are supposed to be neutral safe spaces where knowledge is transferred to students. Today their boundaries have become reservoirs of uncertainty and fear.

Matilde Gattoni

Born in Milan, Italy. Lives in Milan, Italy

matildegattoni.photoshelter.com

Ocean Rage, 2016

“Ocean Rage” is an ongoing project aiming at documenting the devastating natural and social effects of climate change on the coastal communities of West Africa. As a consequence of global warming and sea level rise, more than 7,000 km of coastline from Mauritania to Cameroon are eroding at a pace of up to 36 meters per year, disrupting the lives of tens of millions of people in thirteen countries. While local governments scramble to salvage big cities and industrial complexes, thousands of villages are being left out in the cold, pushing a thousands-year-old way of life on the brink of extinction. Rising temperatures have pushed fish stocks away from the coasts, while erosion and salinization reduce arable land and contaminate freshwater reserves. Deprived of their means of survival, communities lose their most resourceful people to migration. As rampant unemployment drives drugs and alcohol consumption, the only profitable activities left are those controlled by criminal syndicates involved in fuel smuggling and illegal sand mining. Once home to thriving fishing settlements, the coastline of Ghana and Togo is now a sequence of crumbling buildings and ghost towns which have been swallowed by the ocean in little more than 20 years. As climate change wipes away houses, churches and plantations, it also destroys the livelihood, cultural heritage and social fabric of entire communities, with dangerous consequences for the future of the whole continent. The submitted series, shot along the coasts of Ghana, Togo and Benin, is the first chapter of a project spanning thirteen African countries. The next one will bring me to Senegal, Gambia and Guinea-Bissau where, by 2100, 70 percent of the coastal population is projected to suffer from sea level rise, experiencing chronic flooding, increased field salinization and the spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera and malaria. By mapping the destruction in a region where climate change has received very limited coverage, I want to show how the problems haunting West Africa are the harbinger of what mankind will experience if we won't be able to find a viable balance between progress, social inequality and environmental conservation. In a world where progress is synonymous with urbanization and consumerism, traditional communities are being sacrificed on the altar of modernity, even when the increasing pressure on natural resources should prompt an overhaul of our priorities.

Girma Berta

Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Lives in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

www.gboxcreative.com

Moving Shadows, 2015–2016

A Street Photography project where I cut out the street laborers and ordinary people are set against a backdrop of color, illustrating my moments of everyday life and offering imagined interpretation of everyday life. The entire creative process, from capture to editing, to publication, produced within my mobile device.

Girma Berta is a self-taught artist based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia whose work infuses street photography with fine art. Born in Addis Ababa in 1990, Berta studied Information Technology graduating in 2009. His most distinctive style is demonstrated in the Moving Shadows Series in which cutouts of street laborers and ordinary people are set against a backdrop of colour, illustrating his mastery of capturing poignant moments of everyday life and offering an imagined interpretation of everyday situations

Eric Gyamfi

Born in Bekwai, Ghana. Lives in Accra, Ghana

www.ericgyamfi.com

…Just like us…, 2016

Why sexual minorities do exist? Who are they and how do they live like? How different is their everyday lives? And how does that threaten mine? How similar or different are we and in what ways do our lives and experiences intersect? How significant are our differences?

With these questions in mind, “…just like us…” becomes the beginnings of a journal on the lives of queer friends I call participants, and others I meet along the way, who will possibly lend themselves over to this continuous visual record of the mundane, that exists outside of the hetero-normative, yet within it, both as records of their existence and eventually as part of the cumulative history of Ghana. “..Just Like Us…” aims to show Images of fellow human beings.

Sonia Hamza

Born in Paris, France. Lives in Seine et marne, France

www.soniahamza.com

Le jeu de cette famille, 2015–2016

As a French Moroccan woman, I have always look for my roots. As a visual artist I am attracted by the visual genetic sign of my family's heritage. I have always heard my mum telling me "you have the eyebrows of your grandma (dad side)". Because I look very French I was proud to have at least this evidence of my Moroccan roots.

So I began to play with the ID pictures I could collect from both side of my family. And through a simple compositing I realized that I don't have the eyebrows of my grandma, that's a legend but better... I have her eyes. And through my grandma I have the same eyes as my father, my aunt and my uncles. The eyes were my only way (with hugs) to communicate with my grandma because I can't speak Moroccan and she couldn't speak French. But we could understand a lot through our eyes. Especially our love. Beyond this finding that I have obviously a Moroccan part in my face, it's all the transmission of our ancestors, grandparents, parents, and other family members that we know or not, that we still meet or not. The emotional heritage we got when we are born, we are not a blank page, is a sort of genetic and emotional summary of all the older family members. An other way to travel in Time and Space. Genetics do not know human frontiers, do they?

Through this series, I wish I could manage to conjure up questions relating to identity and culture.

I want to keep the ludic aspect of my « exploration ». I don’t want to make these questions more sensitive than they are nowadays. So my series is inspired by a French card game, "Le jeu de 7 famille". You need to complete families, asking the other players to exchange some cards. The winner is the one who complete all his families. To ask a card you say "Dans la famille X, je demande le X".

I do hope to succeed to engage the viewer searching the images for the similarity of features.

Laila Hida

Born in Casablanca, Morocco. Lives in Marrakech, Morocco

www.lailahida.com

Looking for you, 2014

"Looking for you" is a series of metaphoric images that speaks about identity and personal quest and how this laters are buid up through multiple elements and facts that occur in ones life. It is a collaborative project with moroccan design Artsi Ifrach who lives and works in Marrakech and with whom we build a durable dialogue through our respective practices and interrogating each others univers and sensitivity. He comes from a jewish family who lived in the Mellah, old jewish neighbourhood of Marrakech and own an old house that has been empty for many years and where we have found many objects that tels many things abour history and memory of the place that we have used for this story. Together we have questioned our common past as Moroccans from divers confessions but even more as individuals, who are carrying a personal quest in life, history and background.

With this project I have tried to conceived of the photographs all different allegories. In each of these 10 portraits, each character is looking for something: spirituality, a material life, a memory, a new philosophy, a response… But this also can be seen as a result of a long and sophisticated processes of mind control and fabrication of a individual of our current society.

To strengthen this iconic aspect, I used the conventional methods used in studio fashion photography. Against a white background, the model poses with simple and minimalist accessories—a veil, a suitcase, a TV, a branch—in sober black and white colors. This deeply sensitive photographic process reveals these accessories to be symbols of intimate yet universal questioning.

Lebohang Kganye

Born in Gauteng, South Africa. Lives in Johannesburg, South Africa

Ke Lefa Laka, 2013

Family photographs are more than documentation of personal narratives; they become prized possessions, hearkening back to a certain event, a certain person, and a particular time. But they are also vehicles to a fantasy that allows for a momentary space to ‘perform’ ideals of ‘family-ness’, and become visual constructions of who we think we are and hope to be, yet at the same time being an erasure of reality.

Six years ago I lost my mother. She was my main link to our extended family and past since we all now live in separate homes. Her death sparked the need to trace my ancestral roots. I needed to locate myself in the wider family on some level and perhaps also to explore the possibility of keeping a connection with her. The idea of ‘the ghost’ started to emerge in my work. Like a presence that isn’t, of which Roland Barthes speaks about in his book ‘Camera Lucida’: “There I was in the apartment where she had died, looking at these pictures of my mother, one by one, under the lamp, gradually moving back in time with her, looking for the truth of the face I had loved. And I found it”.

I began looking for pieces of my mother in the house. I found many photos and clothes which had always been there but which I had ignored over the years. There she was smiling and posing in these clothes. Unlike Barthes though, I don’t know if I found what I was looking for in these ghostly traces. My reconnection with her became a visual manipulation of ‘her-our’ histories. I began inserting myself into her pictorial narrative by emulating these snaps of her from my family album. I would dress in the exact clothes that she was wearing in these twenty-year-old photographs and mimic the same poses. I later developed digital photomontages where I juxtaposed old photographs of my mother retrieved from the family archives with photographs of a ‘present version of her’ - me, to reconstruct a new story and a commonality – she is me, I am her and there remains in this commonality so much difference, and so much distance in space and time.

My grandfather represents the central patriarchal figure in the project. He passed away before I was born and we carry his surname. He was the first person in the Khanye family to move from ‘di’plaasing’, which means ‘homelands’ to the city to find work because he didn’t want to be a farm labourer like the rest of the family. As apartheid was ending and the majority of the family moved from the homelands to seek work in Transvaal. As a result, everyone in the family has stories about my grandfather. The project is also about being at the same place at different times and not meeting.

In these fictive narratives I am the only ‘real’ person, taking on the persona of my grandfather, dressed in a suit, a typical garment that he often appeared wearing in the family photographs. It is perhaps not surprising that with my father an active absence in my life, I sought to identify with another father-figure and directed this at my mother’s father, dressing in his clothes and ‘walking in his shoes’ (both over-sized). As a young woman enacting a patriarchal figure in a family, I address the shift in my role as a woman, having to be a provider and protector of the family since my mum’s death, This photographic journey seems to be a deep response to loss and mourning – not just of family, but of history, language and oral culture. I have discovered that identity cannot be made fully tangible just like the products of a camera; it is a site for the performance of dreams and the staging of narratives of contradiction and half-truths as well as those of erasure, denial and hidden truths. A family identity therefore becomes an orchestrated fiction and a collective invention. While these images record history, it is only a history imagined. I will choose which part of the fantasy to take with me and claim as my story.

Heba Khalifa

Born in Cairo, Egypt. Lives in Cairo, Egypt

www.heba.photo

Homemade, 2016

“Be careful, you are a girl” these demeaning words summarize my life and my relationship with my body. Ever since I was young girl I was constantly reminded by mother that being a girl is a liability and burden. I need to be extra careful of my actions. I cannot stay out late, what people would say about me. Even when I got divorced I was reminded by my family. “Be careful, you are a girl”. We live all our life guarding our body. You have to get married before you become too old to bear children. You have to preserve your figure to stay desirable. You have to you have to...Entrapped in this body I resented it. I wished to lose it, to live without it.

It starts on a private group on Facebook. Together, a group of women share our feelings and personal stories. Then we meet in person. We discuss what it means to be living with all these pressures, simply because we own this body. We talk about how each of us discovered what it means to be a woman. Faces turn red, tears start rolling and at that moment of openness a magical bond between us is born. From their words I take some time and start visualizing how the image of their story might look.

After I photograph the women, I notice a change. Two women decide to show their faces in the images, something they previously resisted. They do not care about the consequences; they feel liberated.

Storytelling is a way to heal, to free ourselves from the weight of experience. The women who found the strength to stand and speak in front of the camera, this is the real gift. It gives me the strength to photograph and I hope it will give other women who are still silent the strength to open the door.

Francis Kokoroko

Born in Koforidua, Ghana. Lives in Accra, Ghana.

www.franciskokoroko.com

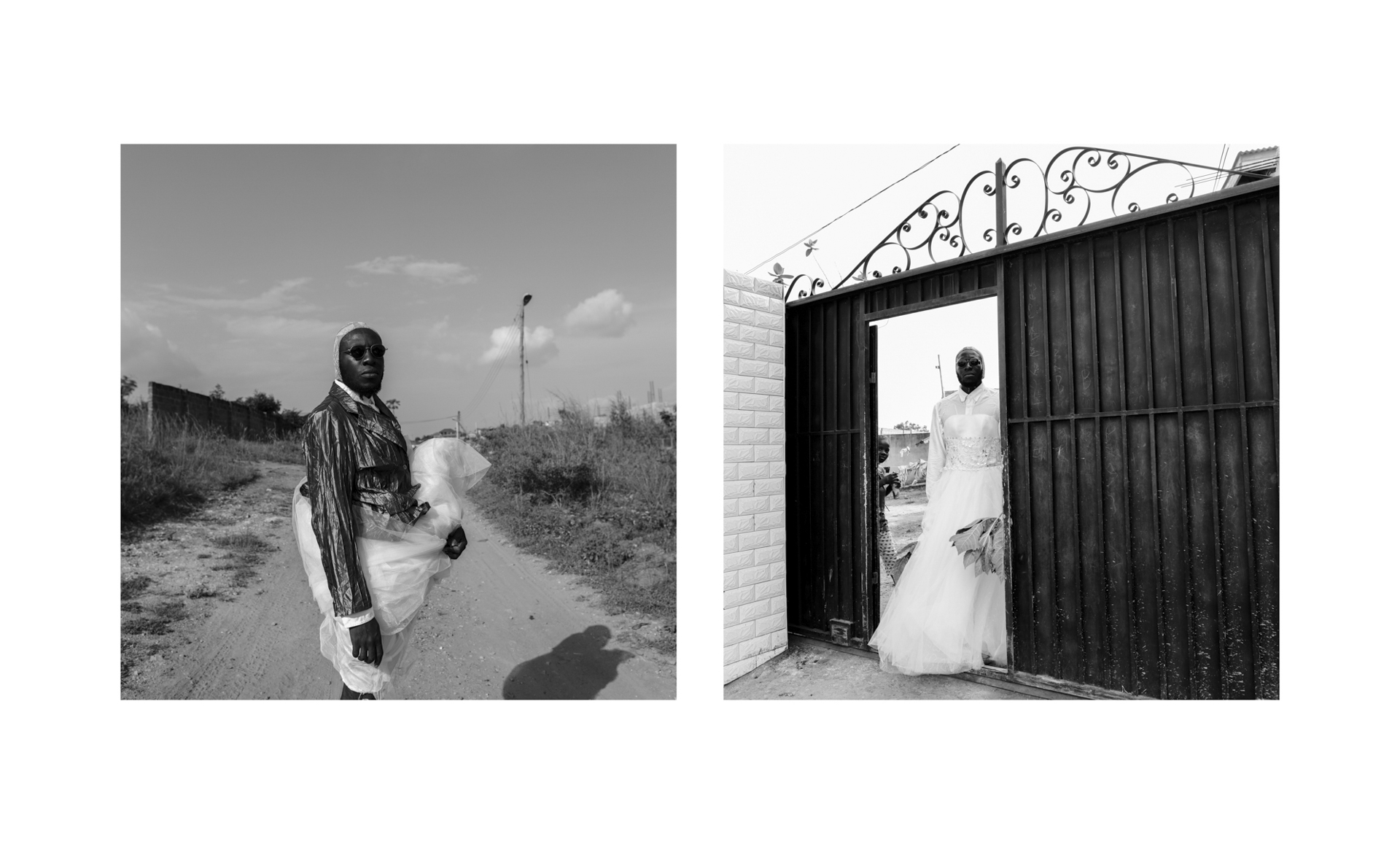

Sui Amantes Sine Rivali, 2016

This set of photos reflects on concepts of Self and Love as performance. The concept of Self, which we have over the years embraced cautiously, now presents itself prominently, disregarding the haunting episode of Narcissus. The series lends its title from the Roman philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero’s description of military leader Pompey as sui amantes sine rivali, a lover of self without rival.

How does Love engage the ‘Self’ or ‘Same’ without reprisal from the other? Is love in itself not a forlorn performance, in a hopeless search of acceptance? Borrowing the ‘white-gown’ as a costume worn by the lover, Steloo stages a performance embodying both the bride and the groom on the day of their matrimony.

Further interrogations come to play about embracing one’s self and sexuality against Africa’s communal and cultural backdrop.

Performer: Evans Mireku-Kissi

Matjaz Krivic

Born in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Lives in Ljubljana, Slovenia

www.krivic.com

Digging the Future, 2014 – 2015

16-year-old Yakuba emerges from a 50-meter deep hole after another gruelling 14- hour work day underneath the panorama of western Burkina Faso. Last year, his uncle and two of his friends died when a nearby mine collapsed. News? Not at all. In this part of Burkina Faso, this is just another day at the "office" for the miners.

Burkina Faso is one of the poorest countries in the world, yet ranks fourth in Africa's production of gold. Much of the gold comes from small-scale mines, where children work alongside their parents from dawn to dusk. They only get paid for the amount of gold they find, and sometimes they won't make any money for weeks, even months. The work is hazardous. Mines collapse frequently, and the working environment is intoxicated with dangerous chemicals like mercury, used in the process of extracting gold.

Unfortunately, there is no gold for Yakuba and his team today. Sometimes it can take up to two weeks to find just the equivalent amount of gold used in one smartphone. Thousands of Burkina Faso's youths live and work on these sites. Most of them have never been to school. For many of them, the mines are their only home. The International Labor Organisation considers mining one of the worst forms of child labor due to the immediate risks and long-term health problems it poses with exposure to dust, toxic chemicals, and heavy metals—on top of back-breaking manual labor.

Men, women, and children dig the mines by hand, and while there are always ropes for the buckets of ore, there are not always ropes available for the boys who scrabble up and down the pits. Finding footholds and handholds in the dirt walls is not a given — but losing your grip can prove fatal. 13-year-old Nuru cannot recall how long he has worked in the mines. He has never been to school and does not know how to read or write. He believes that mining is still better than working on the fields back home where "you farm the land, but don't earn anything."

Government-approved dealers undoubtedly turn a blind eye to the children of the mines who suffer and die dreaming of their very own "El Dorado" for the sake of our smartphones.

Tsoku Maela

Born in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

tsocu.tumblr.com

Barongwa: I am that I am / Abstract Peaces, 2016

Who are you?

Where are you from?

Where are you going?

What is your purpose?

Questions that we have asked ourselves since the dawn of time. Since 1 billion became 6 billion became 7.5 billion people roaming upon the spherical abode.

This comes as no surprise as when you strip away all that is artificial, all that is man-made – money, the constitution of law, social constructs – the true currency that governs man remains: Knowledge. And if indeed we were to separate said currency by region as we do in the real

world, then the most valuable of those currency would undoubtedly be the knowledge of self.

To know yourself, to really know yourself, is to know the very fabric of the universe, to walk between the pages that scribe the secrets of creation and existence. That knowledge is passed down by those who came before and after us, those who watch over us. They are neither man, nor are they God. They are neither here, nor there. They are the guardians, or as we know them Barongwa.

The greatest texts, from the Hebrew writings to the Tibetan book of the dead all seem to agree that we were created in the image of the creator. In return and perhaps man’s greatest fault was to try to create the creator in man’s image – an now does the infinite live within the confines of gender, but they have clothing, a throne, a twisted sense of humor and an irrational temperament towards those who disobey.

But who is this infinite, really? No one really knew the infinite by name (God isn’t a name) until Moses encountered the burning bush (God) and asked it what its name was, upon which the response was ‘I am that I am’.

How profound and boundless can a burning bush be in all its vagueness? To be whatever you so say or wish to be? Could that be the answer to our questions? If you were made in the image of the creator, then surely you too can I am that I am? You too are a creator, and your greatest creation long after you have lived will be your purpose.

But for us to grow from mere babies to enlightened people (self-actualization), we need to go through phases and in this series we look at some of those stages and the relevant characters/guides that show us the way.

Bruno Morais

Born in Rio de Janeiro. Lives in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

www.nobruno.com

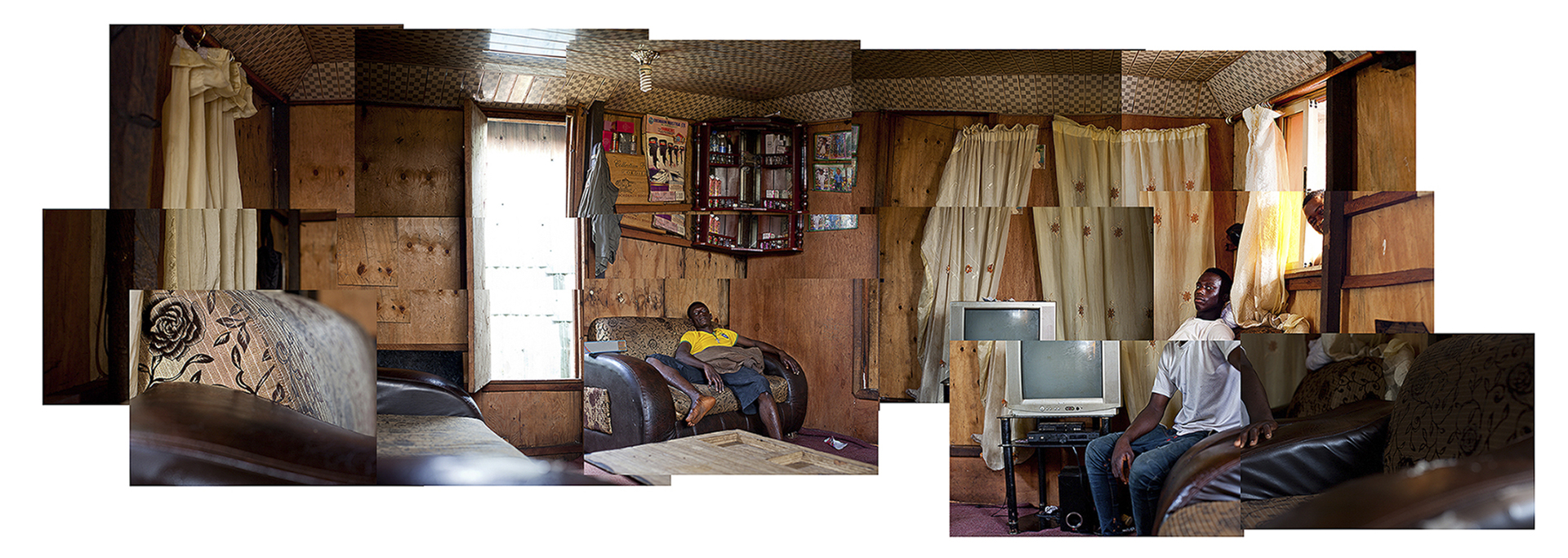

Inside Makoko, 2016

Makoko is one of the most vibrant and yet sadly famous neighborhoods in Lagos. This fishing village turned into floating slum is constantly under the threat of demolition from the Government and his inhabitants have been repeatedly evicted and their houses burnt. The news keep a close eye on the community as a rich source of dramatic news and ocasional photojournalists are frequent in the canoes that break into the narrow canals, but little is understood about the community with these ocasional and superficial approaches. Most of Makoko´s inhabitants migrated from Benin in the search for a better life in the rich neighboring metropolis of Lagos. They brought their habits, their culture and their religion, Voodoo. Their life as immigrants was built with layers, bits and parts of memories and sporadic income. Their houses are the clear reflection of their status and fragility as part of the Nigerian society. With this project I tried to not only give an inside look at the surface of what the news show, but also build images that respect the structural composition of what they depict. With an image resulting from the combination of multiple shots, the result is a complex visual construction that supports the sickly shanty structure of the houses and their owners.

Adriane Ohanesian

Born in Saratoga Springs, New York, USA. Lives in Nairobi, Kenya

www.adrianeohanesian.com

The Forgotten Mountains, Darfur, Sudan, 2015

In the Marra Mountains of Darfur, Sudan, hundreds of thousands of women and children hide in caves to escape ground attacks and aerial bombardment by their own government’s forces. The mountains are now one of the only remaining sanctuaries for the people to hide. The war in Darfur has claimed half a million lives and displaced three million people. The international community has declared genocide in the region, yet the United States has eased sanctions on Sudan, and even as the war continues, it seems that no one is watching.

While the flourishing capital city of Khartoum was funded by oil money from the predominantly Arab government, none of these benefits reached the outskirts of Sudan. The people of Darfur remained impoverished on a scale that few would be able to comprehend: no running water, no electricity, no education, no healthcare. They had nothing to lose by standing up and demanding attention from their government. Native African tribes who called Darfur home clashed with the all-powerful Arab regime of President Bashir. Horrifying accounts of human rights abuses in Darfur led to the indictment of Sudan’s President Bashir by the International Criminal Court with ten counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes, yet he remains in power.

The Government continues to deny the international community, relief workers, the United Nations, and journalists from entering into the rebel-held territory. Embedded with the rebel group the Sudan Liberation Army – Abdul Wahid, my journey to Darfur in 2015 was an expedition that took nearly three years to plan. The information, images, and video footage were the first from the region in nearly ten years, and contributed to further investigations by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the United Nations Panel of Experts on Sudan. I hope that the photographs portray the situation on the ground not only to those outside of Sudan, but also to those in Khartoum, as the images provide evidence of the continuing ethnic cleansing in Darfur which the government of Sudan has worked so hard to deny.

Fethi Sahraoui

Born in Hassi R'Mel, Laghouat, Algeria. Lives in Mascara, Algeria.

www.instagram.com/fethi.sahraoui

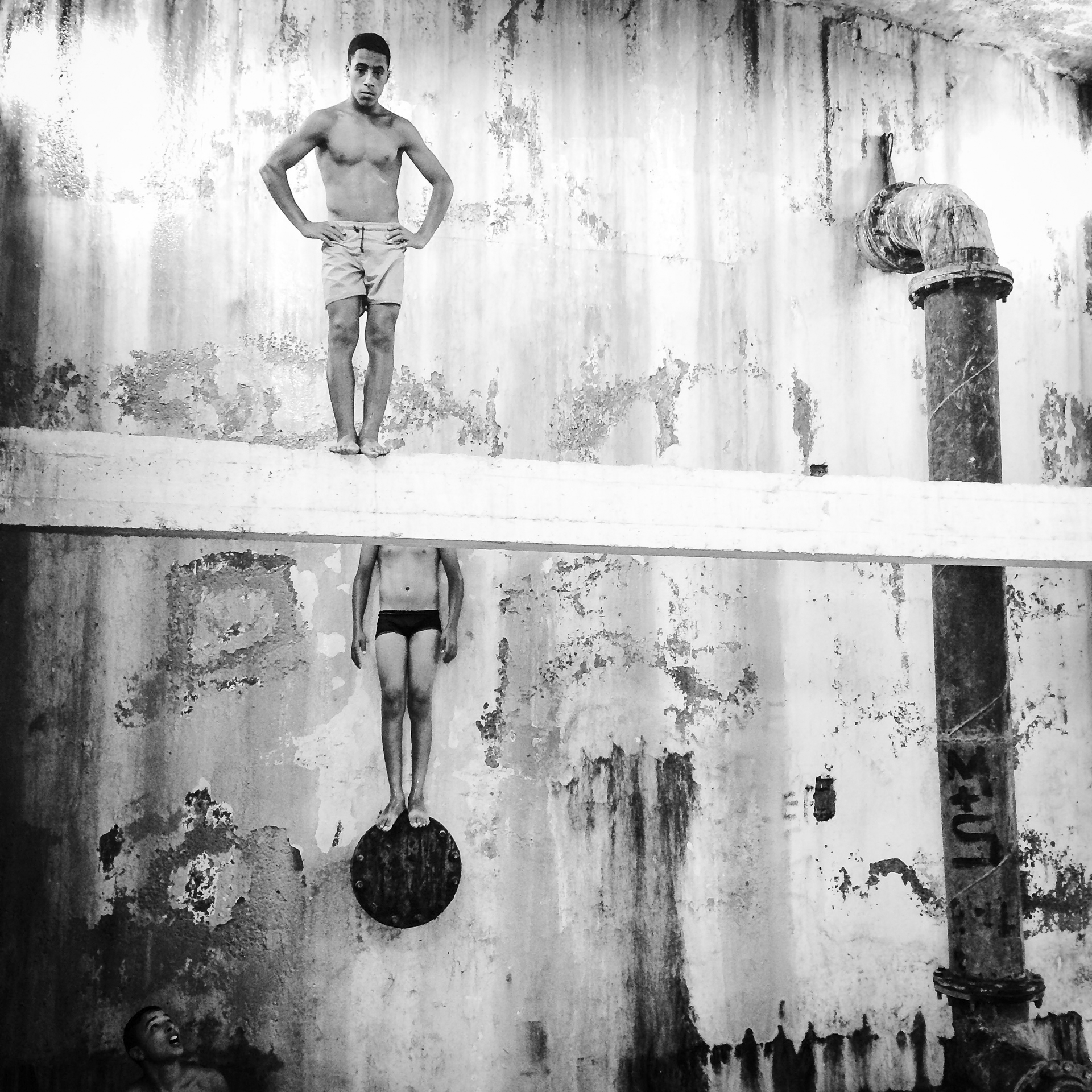

Escaping the Heatwave, 2016

The coming of the heatwave can be synonym to an escapade to the sea for the supermajority of the Algerians because it is the most accessible kind of vacations and the most affordable one.

In places like Mascara and Relizane during long summer days the temperature approaches the 44°C,even if the Mideteranean coast is only 65km away,for some familial and financial reasons not all children will have the opportunity to go spend a day in the beach,as a result of a lack of places of amusement like pools in those parts of the country children manage to escape the heatwave by going to some dangerous spots like an abandoned water tower,there injuries are so common beside the water which can be very polluted,you can find them swimming in large irrigation channels too with some deplorable conditions exposing themselves to countless risks away from their parental supervision.

The aim of this photographic series is to show the plight of these children who are ready to do anything just to avoid a hard sun.

Georges Senga

Born in Lumbumbashi, Congo (Dem. Rep.). Lives in Lubumbashi, Congo (Dem. Rep.)

georgesenga.wixsite.com/georgesengart

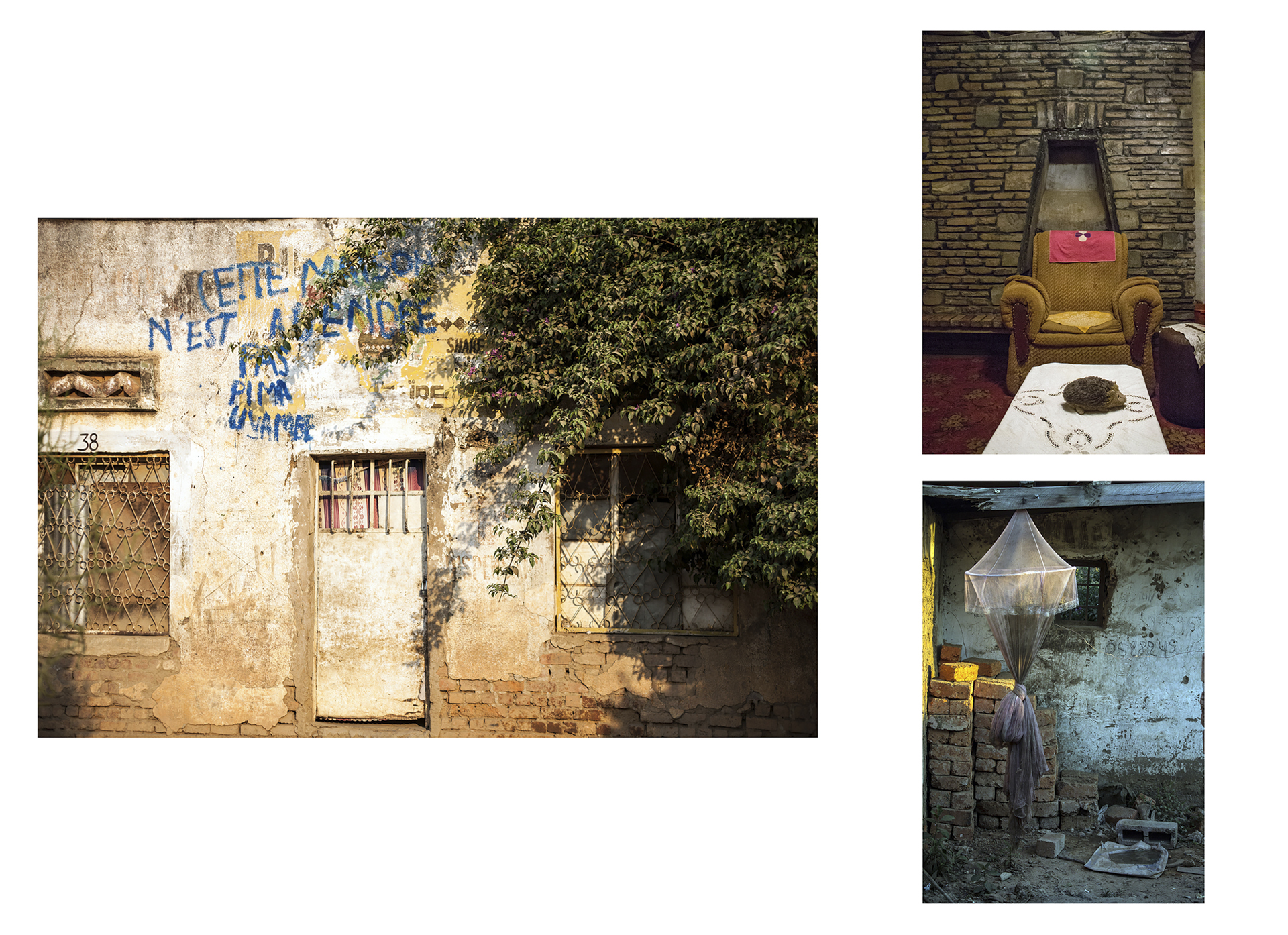

Cette maison n'est pas à vendre et à vendre, 2016

My project speaks of value; in this value I see memory in relation to situations. And these situations refer to the urge to keep or to lose something. The topic for this show first caught my attention when my family home was in the situation of conflicted inheritance in 2009-2010. After that I started taking photographs of the houses in my neighborhood.

In Africa people talk publicly about conflicts of family heritage and although you find those conflicts anywhere in the world they are not presented in the same way as in Africa.

Concerning our family home it was only a short period of time when it was happing, a few family men wanted to sell the house, while the others did not want that at all. The part of the family who were against the sale put great writing with oil paint on the house »this house is not for sale.« This message would be a warning for anyone who would like to interact to buy the house. This was the moment when I started to ask myself, why do people need to write this on their houses publicly…Is it about respect for the memory of the person who leaves you this house as heritage

The houses I have photographed are familiar to me because they are in the neighborhood where I grew up, in the commune of Katuba.

The project is called »this house is not for sale and for sale.« People have two kinds of opinions, some of them agree with selling their houses and some of them disagree: I chose Brazil because I also wanted to explore another way to represent the conflict of heritages.

In DR Congo I photographed the photos of the houses that are not for sale from inside, because seeing the objects from the inside made me get closer to the story of the house and the memory of the owner from who the present owners got the house.

The houses from Brazil are in Praia Grande and they are disappearing because of new constructions of high buildings. The houses »for sale« have memory and history but at the same time they are on view for sale; in that way they are losing their history and memory.

I decided to photograph objects in the areas of those houses to reconstitute the history and the memory of the houses. The object and the houses are on view for people, but the objects are for free and the houses are for sale.

Abdo Shanan

Born in Oran, Algeria. Lives in Oran, Algeria

Diary:Exile, 2016

Every day is struggle to keep dreams alive, even the little ones could be challenging to feed the flam that drives them. dreams give us expectations ,the greater they are the harder are to reach and achieve ;it is a long road mudded with dust sweat and blood.

In this part of the world dreams are hard to pursuit not because they are big but because they are different , in a society where certain tittles and roles are accepted , success is bound to a predefined path with few obligated stops ,a path that flows in one direction with no trace left behind; a system that refuses to accept change and fails to reproduce itself to evolve, every generations is bound to “failure to lunch” ; a reality that might contaminate dreams to a more acceptable variations.

The road is long and the load is big , you find yourself conflicting the main stream fighting against ideas and finally fighting against people around you. Refusing to vanish in a crowed of broken dreams or merge with the grays. Finally exile becomes a stronghold against prefabricated reality a shield that will protect who you are; an exile surrounded with solitude disappointment and fears of ticking time growing old accomplishing nothing but a broken version of own self; fighting soul and doubting mind conflicting each other on every step of the way.

Mahesh Shantaram

Born in Bangalore, India. Lives in Bangalore, India

www.thecontrarian.in

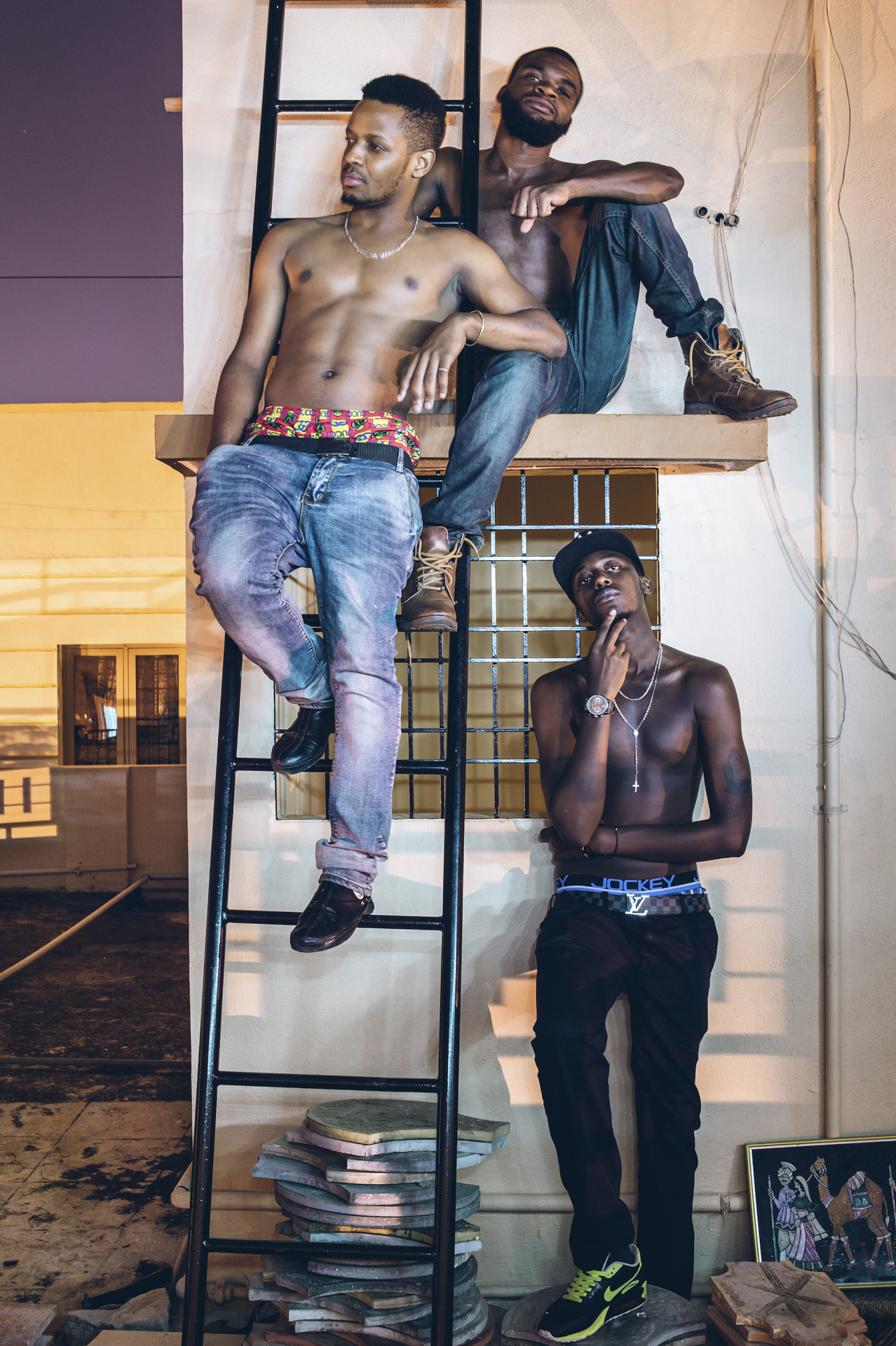

The African Portraits, 2016

On January 31st, 2016, Bangalore woke up to yet another news of a shocking mob attack against a Tanzanian student. This particular one was appalling enough to earn international press, embarrassing India to confront the ugly truth about racism in the country.

In a widely televised debate that followed, one of the more vocal participants kept repeating that this is an aberration in a country that is normally welcoming of all people. As it so happens, this 'aberration' is what Africans suffer as everyday racism.

“It's as if they don't accept us as human beings,” is what I keep hearing amidst all the heartrending stories. “Some of us are from royal families, but here we are treated like shit,” one person told me. This is when I realised that I have a serious project on my hands. There are these students - the best and brightest of Africa who look at India as some sort of mecca of higher education - and they are simply hated for their skin colour. (India is notorious for its fair skin preference for historical reasons.)

Anywhere in the world, it takes a black person to teach us what racism really means.

On my part, since the incident, I've been going out to the far-flung neighbourhoods of Bangalore to meet these African students. I've been learning about their experiences and making portraits as a personal response to give them recognition. I continued my tour to the university town of Manipal and then to the tourist city of Jaipur to meet more African students. I share these on social media with a narrative meant to inform and provoke.

I feel passionately for developing this as a project because it carries such a relevant and urgent message - a country that aspires to be a superpower is at the cusp of coming to terms with good old fashioned racism. Through my project, I seek to put Africans in the consciousness of the Indian public and put racism in present day context.

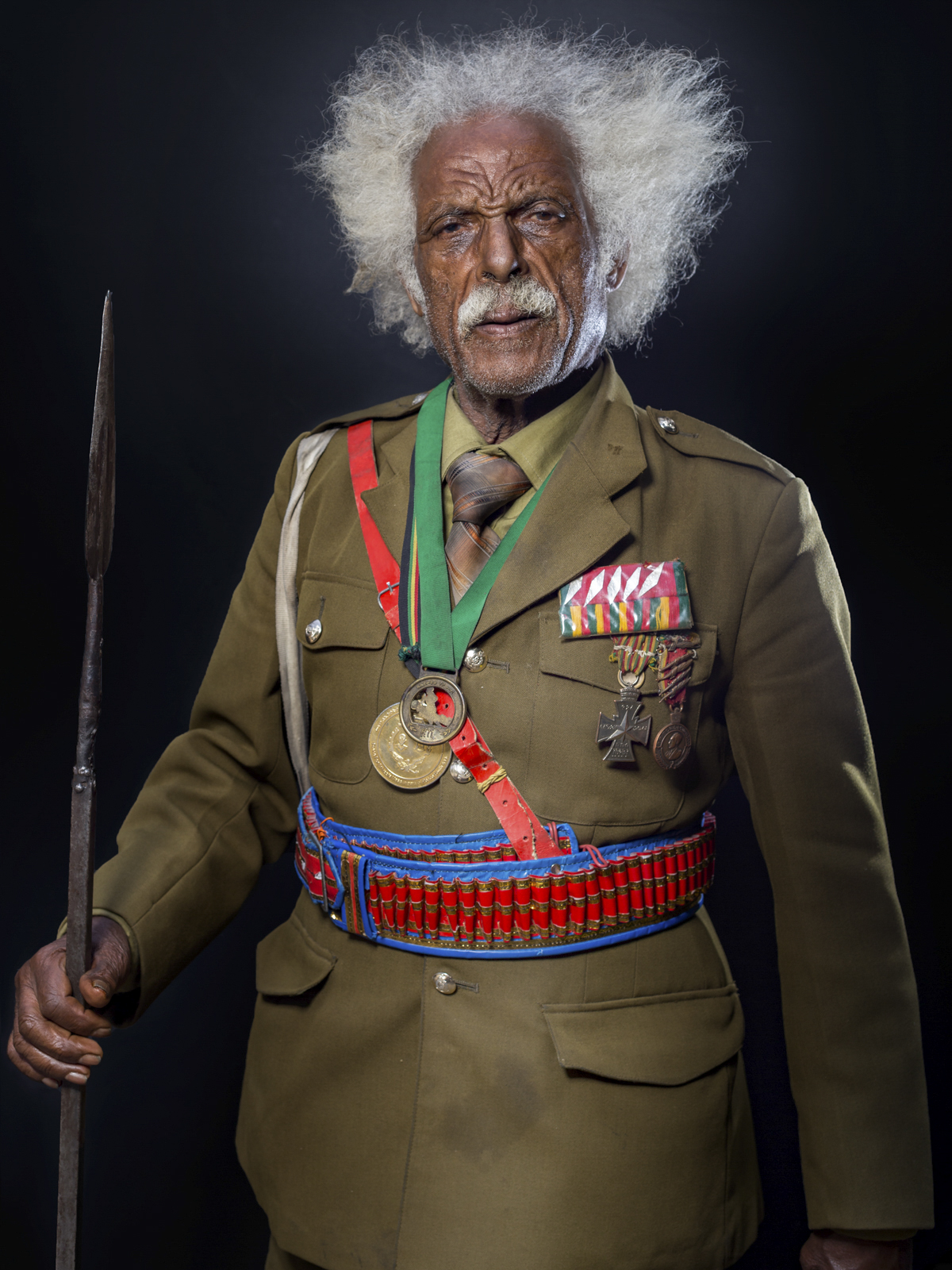

Aron Simeneh

Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Lives in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

The Patriots Story, 2016

‘The Patriot story’ is a portrait series that tells the usually untold stories of the living Ethiopian Patriots that proudly fought against the Italian army during the five year occupation (1935-1941) in Ethiopia under the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini. The inspiration for this series came from my own grandfather who was also took part in the patriotic resistance. I grew up listening to the endless stories he had , but conflicted as I believed I was the only one hearing this rich and beautiful history about liberation. It became clear that if his story and others like his are not documented, we will lose them forever and therefore lose the source of pride in our history that so many Ethiopians rejoice in. In Ethiopian we have a day for which we celebrate our patriots, it is on this day that I am able to talk and hear of the incredibly heroic stories of the men and women who put their lives on the line to fight against the last European colonizers to touch Ethiopia and remain an un-colonized nation. I was fortunate enough take their portraits and to bare witness to the pride they still proudly wore. This series is a salute to our forefathers and foremothers, the warriors who fought and died for our sacred freedom and liberated the heart of our country.

This is their story

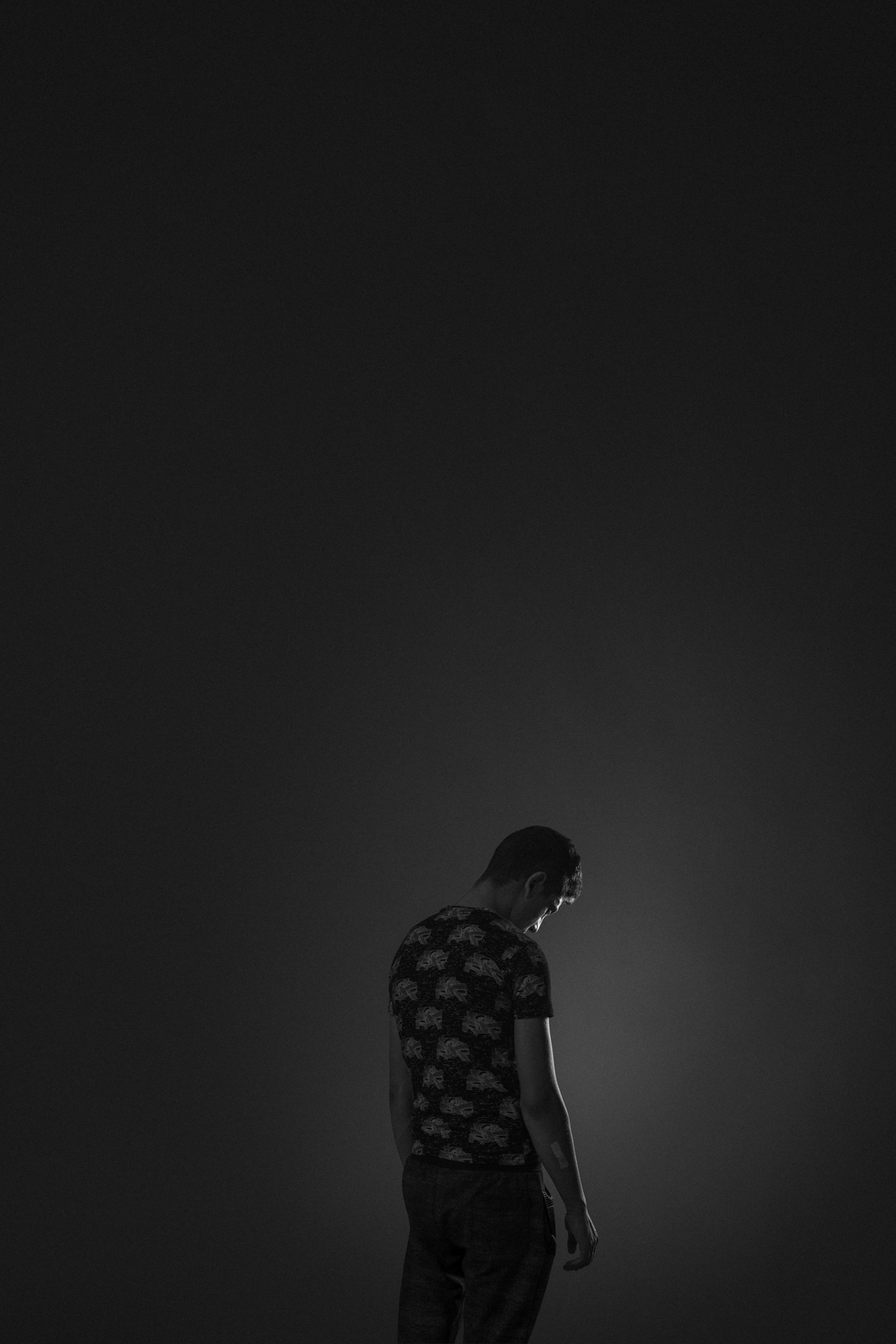

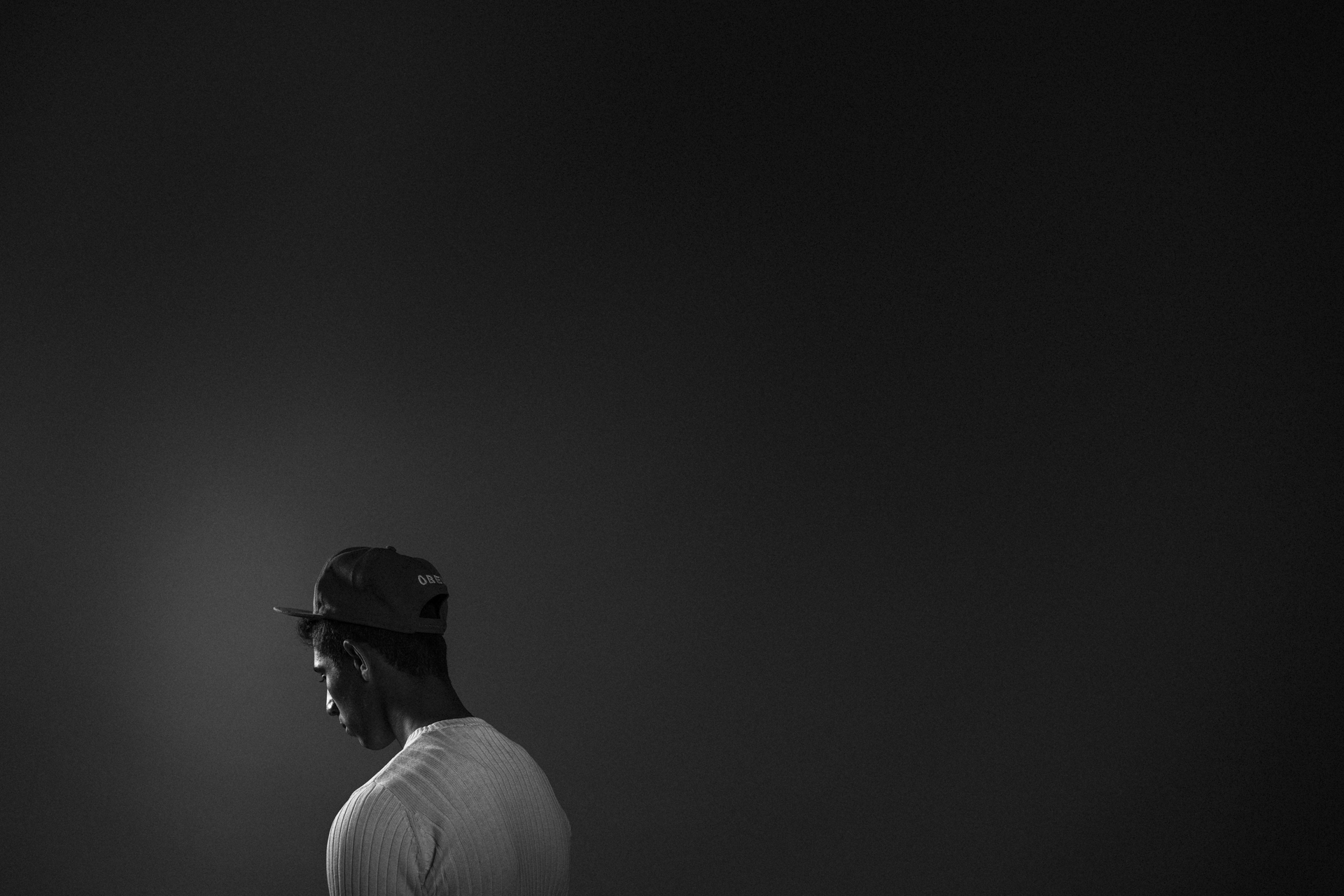

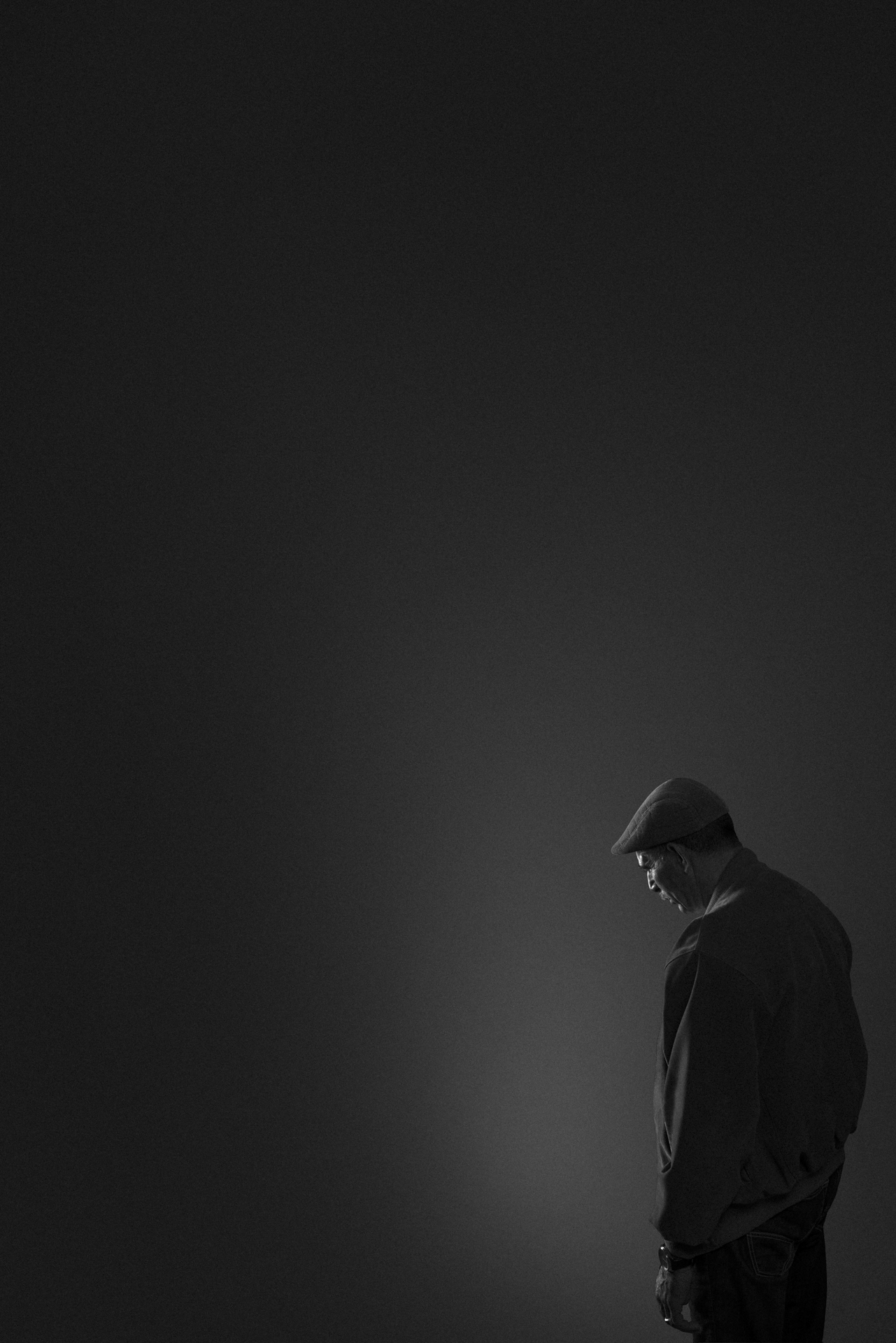

Douraïd Souissi

Born in Tunis Tunisia. Lives in Tunis, Tunisia

www.douraidsouissi.com

Mohamed, Salem, Omrane, Hbib, Hsouna, Alaa, Anouar, Nader, Slim, Ahmed, 2016 – 2017

Breaking News##Portraits of Tunisian men ##Young, not so young and older men ##Ahmed ##Nader ##Omrane ##Hbib ##Mohamed ##Hsouna ##Alaa ##Salem ##Slim ##Anouar ##Looking down ##Away from the camera ##Turning their backs to the camera ##A profusion and ubiquity of cameras ##Of images ##The ease of their diffusion and dissemination ##Made possible by the latest technologies ##Fervent consumers ##Of images ##Constantly asking ##For more ##Sensations ##More!

##These Tunisian men withdrawing ##From our consuming indiscretion ##Our compulsive voyeurism ##There must be more ##If their heads are down ##If they’re doused ##In much space ##Opaque, dark, empty, unnatural space ##There must be more!

##The uprisings of 2010/2011 ##The “Revolution” ##The “Arab Spring” ##The “Advent of Democracy” ##Of “Free Press” ##Of Cameras ##More cameras ##Welcomed at first with open arms ##The “average” Tunisian was eager ##He was proud to face the world ##As the architect of a New Era ##In the transparent, bright, vibrant, virtual space ##Of the www.

##Promises of freedom ##Promises of justice ##Promises of dignity ##Promises of employment ##Promises of prosperity ##Parading politicians parading promises ##Promises of cameras ##Promises of images ##Parading promises.

Antoine Tempé

Born in Boulogne Billancourt, France. Lives in Dakar, Senegal

www.antoinetempe.com

The Ruin of Law, Dakar, 2016

The monumental “Palais de Justice” of the city of Dakar was built in the fifties as an imposing symbol of an efficient judicial system. However, in the late eighties, because of structural issues in some parts of the building, it was determined that the Courts had to be moved to new locations; the building complex was abandoned little by little as the various services were relocated. However, many of the archives, among them numerous legal documents, were left behind along with various furnishings and office apparatus; over time, they ended up scattered among the various rooms of the edifice.

Around 2005, in my first visit to the boarded up building I was struck by the surreal beauty of the expansive rooms strewn with documents and objects; in some rooms, accumulations of papers seemed organized in patterns evoking the waves in an ocean; in other places, the chaos of abandoned objects from daily office life made it look as if the building had been precipitously abandoned following a cataclysm; in other instances yet, it would invoke an art installation.

The organizers of the Dakar Biennial, were also in awe of this edifice when they decided that some parts of the building complex were the perfect venue for the international exhibition of the 2016 edition of the event. Knowing that the Palais de Justice would soon be cleaned up and sanitized, I decided to photograph it; i wanted to keep a trace of this beauty. « The Ruin of Law » is a series of images I took with my digital medium format camera during many photographic peregrinations in the abandoned building.

In my endeavors, as I was getting better acquainted with the edifice and got closer to the documents and the artefacts strewn about, the initial feeling of beauty that had struck me gave way that an other feeling: each fallen document meant a lost case, a broken family, a forgotten birth or death, a forfeited inheritance, . . . The decrepit hallways of the courthouse and their clutter started invoking mostly a feeling of a Justice in ruins.